Alice Meynell: Poetry and essays

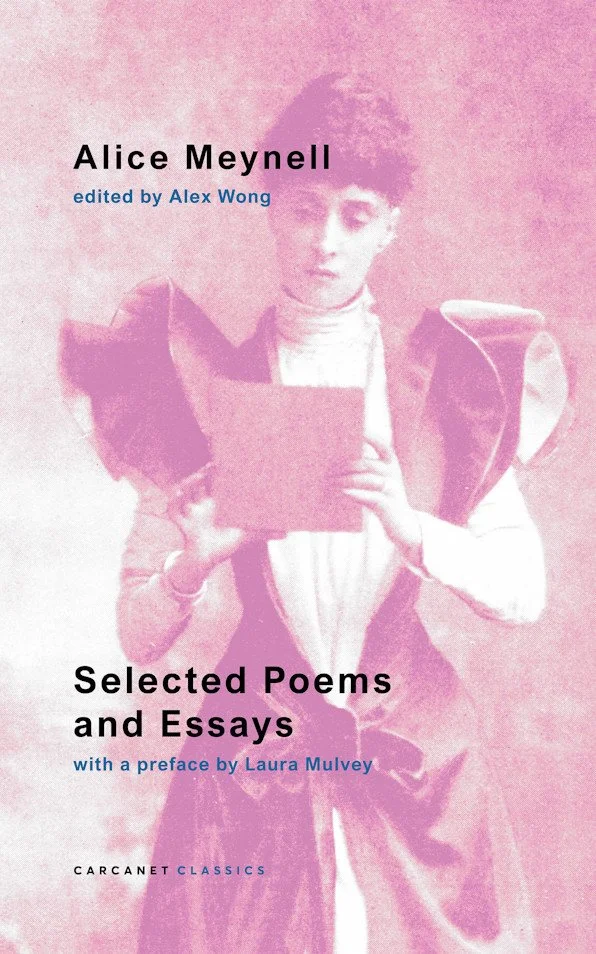

Alex Wong has edited a collection of poems and essays by Alice Meynell (1847-1922), a highly respected and popular poet in her time, but rather neglected since. This is the first collection of Meynell’s poetry and prose since the Centenary Volume of 1947, introduced by Vita Sackville-West.

Alex introduces this important writer, below.

Alice Meynell was an important and eminent English author of her time. Though she has remained in view to some degree during the last century, mainly as a poet and in the pages of anthologies, she deserves greater attention. Meynell is a highly distinctive writer: a brilliant stylist, a hard thinker, insightful and humane, with significant powers of unsentimental poignancy. She has had more than her fair share of the ‘condescension of posterity’, and in editing her Selected Poems and Essays for Carcanet I have hoped, with great support from Laura Mulvey, to challenge that condescension by reintroducing the work itself – in place of the inaccurate, rather drab reputation that Meynell acquired among many readers over the twentieth century.

Her ‘princely journalism’, as George Meredith called it, was prolific but marvellously nuanced and finely composed, touching on a wide range of topics with considerable tonal flexibility. As a poet, she marries firm, lucid thought and deep feeling in a way of her own, as much influenced by seventeenth-century poets as by her more immediate predecessors, and she was a serious contender for the laureateship on two occasions. Passages of even her earliest poetry were called by Ruskin ‘the finest things I’ve seen or felt in modern verse’.

Alice Thompson was born in Barnes, Surrey (now part of London) in 1847 to a middle-class family of artistic and intellectual persuasion. Her mother, Christiana (née Weller), was a talented pianist doted upon at one time by Charles Dickens. She gave up hopes of a musical career when she married, but her artistic sensibility (she also painted and drew) survived and surely influenced her poetical daughter. Thomas Thompson, Alice’s father, had been brought to England as a child from Jamaica, where his father and grandfather had owned sugar plantations. Thomas, the illegitimate son of an illegitimate son, is traditionally thought to have been educated at Cambridge, although this is in doubt. Later, probably because there was ultimately no legitimate offspring to claim the legacy of the Jamaican estates – of slavery, that is, before Abolition in Thomas’s lifetime – he was able to support his family on the inheritance from his grandfather. His mother (Alice’s grandmother), Mary Edwards, is described as ‘Creole’ and was of mixed race, and it is thought that there was mixed ancestry in the previous generation also.

Alice and her sister, Elizabeth (later Lady Butler, a celebrated painter), were brought up in somewhat Bohemian style, mainly in Italy and on the Isle of Wight. In 1868 Alice, following her mother’s example, converted to Roman Catholicism – and fell in love with the young and cultivated Jesuit priest, Fr Dignam, who received her into the Church. A painful break in their friendship was required, and this impossible love inspired several of Alice’s passionate early poems. The most famous of these is the sonnet ‘Renouncement’, which began to be anthologised quite early and has stayed in circulation. It is among her most immediately accessible poems. Here it is in full as a first introduction (as it has been for many readers) to Alice Meynell’s verse.

Renouncement

I must not think of thee; and, tired yet strong,

I shun the thought that lurks in all delight—

The thought of thee—and in the blue Heaven’s height,

And in the sweetest passage of a song.

O just beyond the fairest thoughts that throng

This breast, the thought of thee waits hidden yet bright;

But it must never, never come in sight;

I must stop short of thee the whole day long.But when sleep comes to close each difficult day,

When night gives pause to the long watch I keep,

And all my bonds I needs must loose apart,

Must doff my will as raiment laid away,—

With the first dream that comes with the first sleep

I run, I run, I am gathered to thy heart.

‘I must not think of thee’. ‘I must stop short of thee the whole day long’. Yet between those two lines, which begin and end the octet with the same resolution, the figuration changes subtly: it is not she, the speaker, who must keep herself from moving close to this thought – the thought of the beloved – but rather the thought itself that threatens to come upon her. It ‘lurks’, as if with dubious intent; it ‘waits hidden yet bright’, as if glinting in the shadows; and ‘it must never, never come in sight’. The thought, the internal beloved, with a life of its own that is not that of the real beloved, has its unpredictability, a vaguely sensed and uncertain motive. This expresses very well the ambiguous dynamics of the inner world, the tension of will and desire, and the situation in which even the good becomes almost menacing when it may neither be possessed nor forgotten.

The sestet that follows is a technical marvel of poetic movement, convincingly expressive of the struggle of conscious willpower to cope with the flooding power of what cannot always be kept at bay. Four lines, all single-moulded utterances that, significantly, do not run on but accumulate deliberately, deliberatively, their one central thought – amplifying, explaining, refiguring it – set up the tension: as if she were repeating and prolonging the thought, excusing her dreaming self as much as possible while postponing the dream for as long as possible.

Sleep cannot be resisted, she ‘must’ loosen the bonds of the conscious mind, she ‘must’ take off her will as if she were taking off her daytime clothes (a courageous image). In the final two lines, as sleep takes over and the unconscious begins its fuller reign, the tension releases. ‘With the first dream that comes with the first sleep’ – (is the drawn-out, repetitive phrasing of this beautiful line of monosyllables mere passionate emphasis, or the last, dissolving attempt to hold out?) – ‘I run, I run, I am gathered to thy heart’. Running as a river runs to the sea, or as a dye runs when it comes unfast, running passively, helplessly, in the medium of sleep or with its altered gravity. But also, of course, running as people run, actively, intentionally, to a goal. The repetition brings out both senses, the tension and confusion of agency. ‘I run’, ‘I am gathered’.

*

Alice Thompson’s first volume of verse, Preludes, was published in 1875 with illustrations by her already famous sister. She omitted ‘Renouncement’, which perhaps seemed too personal and revealing at that time, although in later life it was the only one of her early poems that she did not seek to renounce as immature. She was an exacting critic of her own works, but this was based in critical convictions, not false modesty; she knew her strengths and was confident of those literary merits of which she could feel sure. In youth, even before she had published any of her poems, she wrote to the Irish poet William Allingham (‘Up the airy mountain, down the rushy glen’), inviting him to be unsparing in his critique of her work. She did not want ‘praise’ but ‘hard words’ about her faults. As examples she lists a number of artistic sins, including ‘sickliness, want of tone, indefiniteness of expression’. But a parenthesis inserted just here strikes a note, even as early as that, of pride and confidence in one area: ‘(indefiniteness of thought I won’t admit)’. Her clarity and tenacity of intellectual grasp was already notable, and she knew it.

Her poems mix sensuous, post- or late-Romantic lyricism with remarkable conceptual precision and significant demand upon the reader’s brainwork. Her poems are often based in a single, strikingly coherent movement of thought, in many cases appropriately called ‘conceit’, so that one can sometimes feel strongly the influence of the ‘Metaphysical’ and ‘Cavalier’ poets she loved. More habitually and obviously cerebral than Christina Rossetti, with whom she is often compared, her intellectual lyricism is perhaps closer to that of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

In the year following the publication of her first book, Alice Thompson met Wilfrid Meynell (the name rhymes with ‘fennel’), a young journalist and fellow Catholic convert who wrote to her in admiration after having read a review of Preludes. They married in 1877. Alice and Wilfrid worked both jointly and independently on various journalistic tasks, co-editing and copywriting for several periodicals as well as writing literary and critical essays, signed and unsigned, for others. Wilfrid was more involved with Roman Catholic journalism while Alice produced, sometimes at great speed, literary essays of superb artistic sophistication, as well as more occasional and topical pieces. The Meynells had eight children, of whom one died in infancy. Several of the Meynell children became involved in literary life: the best known are Viola Meynell, an author of fiction (and her mother’s first biographer), and Francis Meynell, a poet and left-wing newspaper editor, who co-founded the Nonesuch Press.

Approached by the Catholic poet Francis Thompson, a homeless opium-addict seeking publication, Wilfrid and Alice Meynell published and promoted his work and supported him financially and morally for the rest of his life. They are now known to many readers for their patronage of Thompson, the author of ‘The Hound of Heaven’, more than for their own literary achievements. A 2016 article on the poet, critic and ‘Inkling’ Charles Williams, who in his early years was a protégé of Meynell’s, sounds a familiar note, referring to her as ‘the Catholic versifier, critic and protector of poets’. (1) Thompson would certainly have tolerated none of this condescension towards one of the finest writers of the age, as he thought her. And she inspired deep admiration and passionate devotion in many literary contemporaries besides Francis Thompson – the most passionate of the literary friends (or admirers, in more than one sense) included the Catholic poet Coventry Patmore, the great poet and novelist George Meredith, the Irish poet and novelist Katherine Tynan, and a now little-known American poet, Agnes Tobin, with whom Meynell toured the United States, lecturing and reading to enthusiastic audiences in full halls.

Meynell was known in her own time primarily as an essayist, especially from the 1890s when her prose pieces began to be collected into books. The republication early in the same decade of her poems from the 1870s, with a small number of more recent ones added to them (there would later be more), also raised her reputation. But by far the bulk of her output was in prose, and there were many who regarded her prose style as her greatest and most distinctive achievement. The essays have, however, been much more neglected by modern readers than the poems.

For some years in the 1890s, among the many other reviews or articles she published, Meynell kept up a weekly unsigned column in The Pall Mall Gazette. These essays on various topics, though written fairly rapidly, are brilliantly subtle works of art, and many of her best pieces originated in that series. George Meredith, as I have said, called it ‘princely journalism’, and I would like to end with a generous extract from one of the essays he especially praises, ‘A Woman in Grey’, which shows, in Meredith’s view, ‘how closely the writer feels with her sisterhood and for the world of the time to come’. Several acute readers have told me lately that Meynell’s prose sometimes reminds them of Virginia Woolf, and this essay is one that has been mentioned as particularly presaging something more familiar, despite the great gulf in sensibility, from the younger and now more famous author. It is an essay also singled out also by Laura Mulvey, the feminist critic, theorist and film-maker (and great-granddaughter of Alice Meynell), who writes about it in the preface to my new edition. The woman described in the essay, cycling in the busy traffic of central London, ‘acquires implications beyond herself’, Mulvey writes:

she stands for the way the female psyche had been, and must continue to be, reconfigured in order for mobility to displace stasis. Furthermore, in the same spirit, in her progression along Oxford Street, the bicyclist represents the Movement, the ongoing struggle for Women’s Rights, the politics of progress with which Alice Meynell so deeply identified.

It may be worth noting here that Meynell was President of the Society of Women Journalists and Vice-President of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League, and that that she was, as Mulvey suggests, an outspoken advocate for the rights of women and children.

Here, then, to end, is Meynell’s ‘Woman in Grey’ on her bicycle.

A Woman in Grey (first published in the Pall Mall Gazette, February 1896. This version was published in Alice Meynell, The Colour of Life and Other Essays, 1896)

She had an enormous and top-heavy omnibus at her back. All the things on the near side of the street—the things going her way—were going at different paces, in two streams, overtaking and being overtaken. The tributary streets shot omnibuses and carriages, cabs and carts—some to go her own way, some with an impetus that carried them curving into the other current, and other some making a straight line right across Oxford Street into the street opposite. Besides all the unequal movement, there were the stoppings. It was a delicate tangle to keep from knotting. The nerves of the mouths of horses bore the whole charge and answered it, as they do every day.

The woman in grey, quite alone, was immediately dependent on no nerves but her own, which almost made her machine sensitive. But this alertness was joined to such perfect composure as no flutter of a moment disturbed. There was the steadiness of sleep, and a vigilance more than that of an ordinary waking.

At the same time, the woman was doing what nothing in her youth could well have prepared her for. She must have passed a childhood unlike the ordinary girl’s childhood, if her steadiness or her alertness had ever been educated, if she had been rebuked for cowardice, for the egoistic distrust of general rules, or for claims of exceptional chances. Yet here she was, trusting not only herself but a multitude of other people; taking her equal risk; giving a watchful confidence to averages—that last, perhaps, her strangest and greatest success.

No exceptions were hers, no appeals, and no forewarnings. She evidently had not in her mind a single phrase, familiar to women, made to express no confidence except in accidents, and to proclaim a prudent foresight of the less probable event. No woman could ride a bicycle along Oxford Street with any such baggage as that about her. […]

She had learnt the difficult peace of suspense. She had learnt also the lowly and self-denying faith in common chances. She had learnt to be content with her share—no more—in common security, and to be pleased with her part in common hope. For all this, it may be repeated, she could have had but small preparation. Yet no anxiety was hers, no uneasy distrust and disbelief of that human thing—an average of life and death.

To this courage the woman in grey had attained with a spring, and she had seated herself suddenly upon a place of detachment between earth and air, freed from the principal detentions, weights, and embarrassments of the usual life of fear. […] She put aside all the pride and vanity of terror, and leapt into an unsure condition of liberty and content.

She leapt, too, into a life of moments. No pause was possible to her as she went, except the vibrating pause of a perpetual change and of an unflagging flight. A woman, long educated to sit still, does not suddenly learn to live a momentary life without strong momentary resolution.

Selected Poems and Essays of Alice Meynell, edited and introduced by Alex Wong with a preface by Laura Mulvey is published by Carcanet in August 2025. Paperback, 216 pp., £16.99.

Available from Bookshop.org UK and Blackwells. Please support independent booksellers and book shops.