Elizabeth von Arnim: The Unexpected Modernist

Isobel Maddison writes about a new book of essays on Elizabeth von Arnim

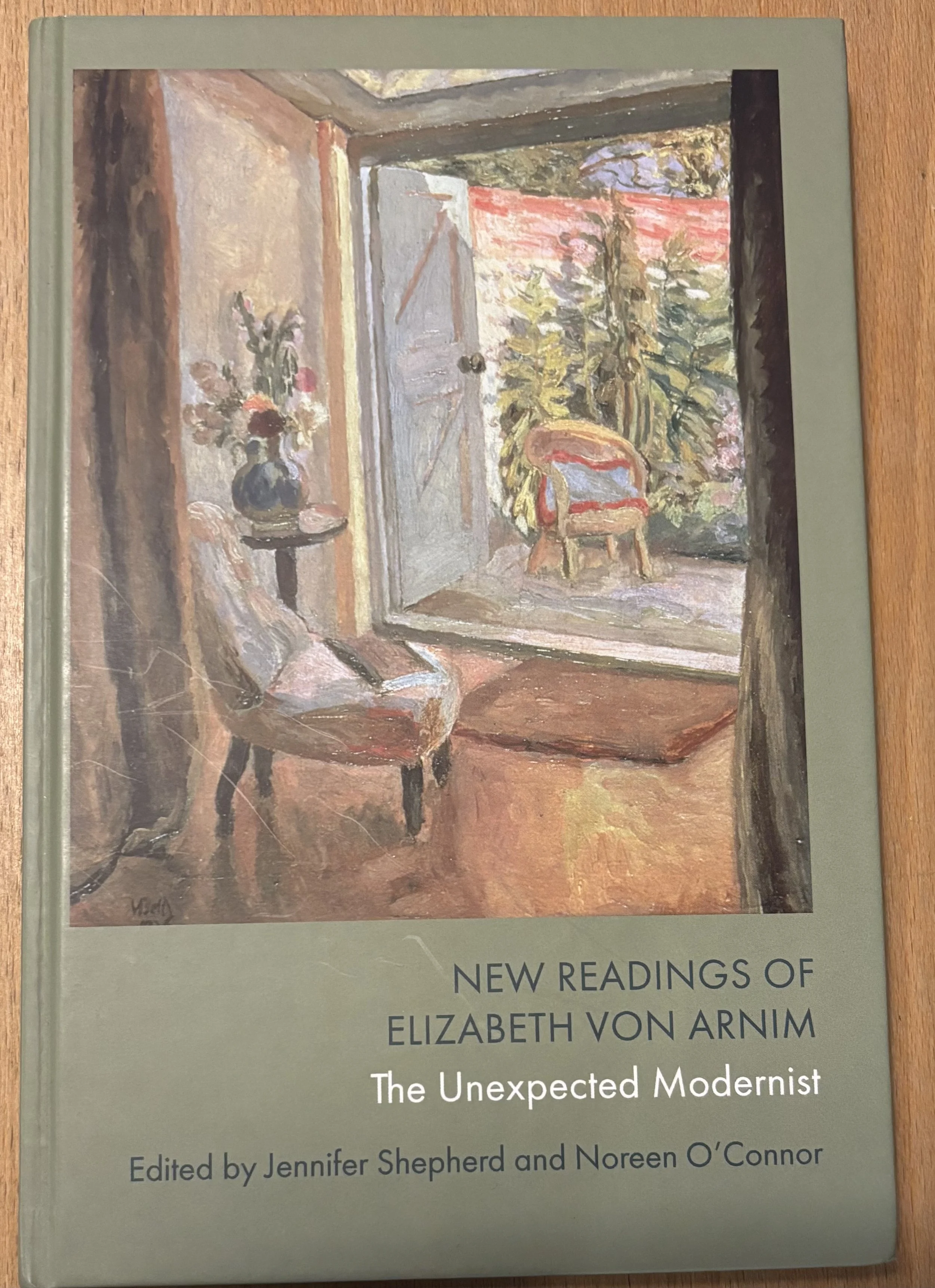

I am delighted to see a new book on Elizabeth von Arnim featuring a range of familiar, and fresh, voices writing on a variety of topics, edited by the excellent Jennifer Shepherd and Noreen O’Connor. Warm thanks to Edinburgh University Press, who have been increasingly supportive in helping raise the profile of Elizabeth von Arnim in recent years. The new book, New Readings of Elizabeth von Arnim: The Unexpected Modernist is terrific, and is sure to develop our understanding of the complexity of von Arnim’s work.

Over the years, scholars have grappled with the problem of literary classification, attempting to read von Arnim in tandem with other authors (Elizabeth Bowen, Katherine Mansfield, Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte and so on), as we’ve wondered if we can ‘fit’ von Arnim into existing groupings to help raise her profile. The contemporaneous reviews of von Arnim’s work make clear just how risky a task this is, largely because of the generic complication of von Armin’s hybrid work, its intertextual depth, its focus on readership and its comic peculiarity, and this is without accounting for the development of her approach and style across decades.

Von Arnim’s writing defies easy classification and, as O’Connor and Shepherd argue in their introduction, ‘The conversations about’ von Arnim’s ‘designation are a reminder that the way critics classify literary works has an effect not only on how we read books but also whether we read them at all’. (p. 26) Additionally, von Arnim frequently includes an irreverent knowledge of past writers and literary traditions in her work, poking fun (most notably in The Enchanted April) at the range of distinctions between low, middle and highbrow that reflect a hierarchy of classification used by critics to categorise writing in the early 20th century and beyond. She resists the notion of fixed approaches, preferring, she writes, the ‘tonic properties’ of a carefully applied and ‘astringent pen’. ‘So much better not to write like anyone but oneself’, she concludes.

So, it has been difficult for scholars to categorize von Arnim’s work. For years, we’ve considered von Arnim as a middlebrow writer, catching a wave of interest created by a seminal study and by academic publishers. We’ve thought about her allegiances with Broadbrow literary production and, at a more granular level, her early work as anti-invasion literature and the imperial adventure story; as a kind of ecological writing; as female escape narratives, as travel writing; as domestic novels sometimes shaded by Gothic leanings; as fairytales; as serialised fiction. She has been read as an author interested in the complexity of gender politics, something we’ve rightly become hesitant to call uncomplicated ‘feminism’, even as we acknowledge her exploration of women’s lives throughout her work. We are pretty much agreed that it is the most continuing preoccupation throughout her ouvre. And now, in 2025, we have a fine and welcome new critical edition where von Arnim’s modernist tendencies are expertly uncovered.

Arguably, in our attempts to make Elizabeth von Arnim relevant again to a fresh generation of readers, to reveal the seriousness of her writing alongside her wit and humour, we have repeatedly raised questions about whether she corresponds to any one artistic category. It seems to me, as a community of scholars, as we have ranged across the variety of work she produced between 1898 and 1940 and, as we have systematically contextualised it historically, occasionally nationally, intellectually and socially, we have discovered her writing exceeds any one label we have chosen to apply at a particular moment, and this is before we add in geography, a pathway for fresh research suggested by this new book.

Von Arnim is too often regarded as a rural writer, preoccupied with gardens and the natural world. But she is also much engaged with the city. We might think of The Pastor’s Wife (1914) where the character, Ingeborg, escapes the drudgery of life as the Bishop’s assistant, heading to a London dentist with tooth ache, to find herself literally tingling with excitement brought about by time spent alone wandering the buzzing streets and lively restaurants, as the city opens up the potentiality of other spaces. Or Millie’s journey of self-awareness in the novel, Expiation (1929), where London’s Bloomsbury provides escape from stifling suburbia, mainly as a positive feeling of nostalgia before becoming a present, rather disappointing, reality.

In early conceptions of modernism, the city features largely; the site of noise, speed, innovation, de-individuation, the blasé attitude and complicated progress. We may not initially think of von Arnim’s writing as directly engaging with these ideas, or with the variety of modernist manifestos that emerged during the early years of the twentieth century, but as O’Connor and Shepherd argue, von Arnim is ‘a writer who uses her fiction to engage with women’s experience of modernity in real time’ (p. 12).

From von Arnim’s correspondence, journals and writing, we know that she was familiar with the broad conceptual thought that accompanied modernism as it emerged in the early 20th century. She also witnessed the progress of experimental modernism as an international art movement and recognised its increasing ability to displace, critically, writing like her own. Her literary instincts were keen too. She bracketed together early, for example, Mansfield and Woolf, and considered a day reading ‘Virginia and Katherine’ as ‘one shot through with radiance’.

Her letters also demonstrate an active knowledge of Joyce, Proust, E. M. Forster, D. H. Lawrence and Rebecca West, among others. And, crucially, from von Arnim’s use of intertextual allusions alone, we know she was able to ‘situate’ these modern approaches in a long continuum where variant forms may have refracted recurring ideas into differing shades of meaning without necessarily altering the fundamental premise of the discussion, or varying the underlying questions raised by the content of the writing.

This new book is alert to these matters while also including a discussion of formal qualities as part of the project to position von Arnim’s writing as unexpectedly modernist. The attention to the use of focalised narrative and free indirect discourse in some of the chapters is especially illuminating.

There are, I think, other stylistic techniques found in von Arnim’s later work that are similarly revealing, such as her handling of time. In The Enchanted April (published in 1922, an enormously significant year for British literary modernism, when Joyce’s Ulysses, TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, and Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room appeared), von Arnim experiments with narrative time, and not for the first occasion.

In this novel, the narrative is focussed on the intricacies of psychological time with its non-linear progress, reliance on individual memory and internal reflection. The Enchanted April is akin to Woolf’s use of time in her writing, though different in technique, von Arnim skilfully creating a long, internal narrative moment hovering empty before an unclear future.

And in the more serious parts of Vera, published in 1921, von Arnim chooses a condensed temporal frame for specific episodes that have more in common with a modernist short story than a comedic novel, as she intensifies the action in the new marital home by concentrating on ‘the dark places of psychology,’ again, to quote Virginia Woolf. The effect is that, within what feels like an extremely long three-day period, the protagonist Lucy becomes identifiable with earlier literary heroines who are systematically victimised. At the same time, familiar gothic tropes are modified, bringing T. S. Eliot’s ‘historical sense’ into a working reality, extending Vera beyond surface meanings into an intertextual and resuscitated past.

Similarly in Expiation (1929), a novel we know von Arnim was writing as she read Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927), we find broadly comparable topics in both books, but communicated through differing techniques and tones.

To the Lighthouse is, in part, a retrospective account of family life before the Great War, and the first part of the book offers an archetypal 19th-century marriage marked by deep affection and personal tension, communicated largely through indeterminate, sensory diction that represents non-linear interiority by mimicking it. Essentially, the narrative style is mimetic. Von Arnim’s Expiation differs, being largely satiric, marked chiefly by the description of non-linear interiority rather than the mimicking of it, the narrative peppered with moments of free indirect speech, declarative statement and omniscient comment as social conventions are highlighted only to be systematically dismantled, as in Woolf’s novel.

These are just starting points for uncovering in the future von Arnim’s possible affinities with modernism and its practitioners.

Elizabeth von Arnim: The Unexpected Modernist is a landmark book, and the editors, authors and publishers are to be congratulated. The book is ambitious, using close textual analysis and the shifting definitions of modernism to convincing effect. The express aim is to extend the parameters of scholarship on von Arnim, arguing for the establishment of Elizabeth von Arnim Studies, and, to this end, the book ranges widely, bringing together established scholars with new voices in the field.

The early chapters revisit some of the most familiar critical contexts for von Arnim’s work – first wave feminism, nationalism, embodied femininity and literary gender – but with fresh eyes, in a section titled ‘Returning to Elizabeth: Gender, Politics and Genre’. It is extremely pleasing to see some of von Arnim’s less well-known novels given a scholarly airing here, and there are some interesting and unexpected pairings too. Wonderful to find an analysis of previously unearthed manuscript material.

The second section of the book, ‘Re-imagining Elizabeth: New Critical Directions,’ offers original readings on fashion, children’s literature, musical composition, the philosophy of aesthetics and literary sociology, all of which offer innovative contexts that stretch our perspective on von Arnim’s achievements, and open new lines of enquiry for future scholarship.

In section three, ‘Reading Elizabeth; Reading Others’, several scholars explore von Arnim’s affinities with modernism and contemporary modernist writers, creating new associations and widening the scope of von Arnim’s reach.

In their entirety, the chapters in this book offer readers ‘the opportunity to get to know Elizabeth von Arnim and her work better, prompting a deep understanding of her relationship with genre, class, gender roles, national identity and aesthetics’ (p. 12) Above all else, the editors tell us, the volume has been designed ‘to encourage new and returning readers to approach von Arnim’s work with an eye for its intellectual richness and its social engagement, as well as the pleasure it inevitably gives’. (p. 12) Bravo. It is a success on all these fronts and a book worthy of von Arnim’s considerable talents.

Jennifer Shepherd and Noreen O’Connor, eds., New Readings of Elizabeth von Arnim: The Unexpected Modernist (Edinburgh University Press, 2025). Available from UK Bookshop.org and Blackwells. Please support independent bookshops whether online or in person.

Isobel Maddison is an Emeritus Fellow of Lucy Cavendish College, Cambridge, and editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Elizabeth von Arnim, The Enchanted April. ISBN 978-0198859093. She is co-teaching a live online course on Elizabeth von Arnim with Juliane Roemhild for Literature Cambridge in autumn 2025.

Cover image: Henri Matisse, The Conversation, 1908-12.