Subtlety and Strength in 20thC women’s fiction

The postwar struggle for freedom in women’s fiction

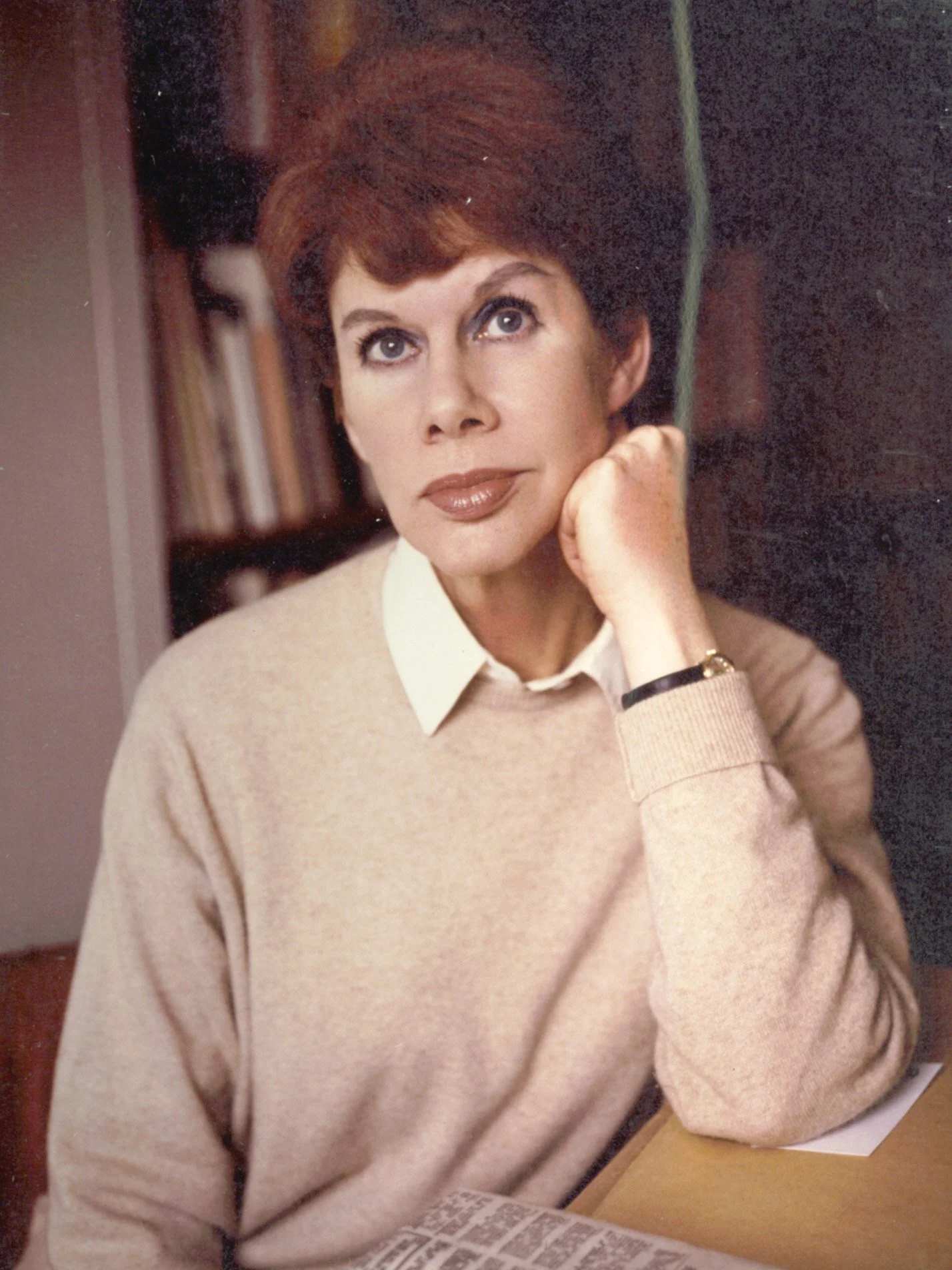

Miles Leeson reflects on the women writers we will study in his new course on Women and Power: 1950s-1980s.

Charting the evolving roles, aspirations, and limitations of women in the social landscape of the mid to late twentieth century, our five writers highlight the tensions within the domestic, fantastic, and communal worlds in which their works are set. We will study brilliant novels by Elizabeth Taylor, Rumer Godden, Angela Carter, Alice Thomas Ellis, and Anita Brookner.

Across the texts chosen for this course, power and agency emerge as central concerns in both private and public settings. Whilst some novels included are overt in their reconceptualisaton of women’s historic disempowerment, others are far more subtle. This course will cover the broad expanse of women’s writing in the post-war era in terms of theme, genre, and locale.

Each of the five novels included gives a significantly different vision of what female agency might mean in fiction. The earliest, Elizabeth Taylor’s Angel (1957), looks back at the Edwardian period focussing on the self-absorbed – and titular character – Angelica (Angel) Deverell, who believes that she can create purely from her imagination without knowledge of what she describes and, crucially, without reading the work of others. Drawing her inspiration from the immensely popular (although now rather forgotten) author of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Marie Corelli, Taylor produces a metafictional work that reflects on how desire can alleviate forms of mental suffering – Angel ultimately obtains entry to ‘Paradise’ – but can also cause us to believe in our own self worth and ego. Angel’s works are adored by the general public but scorned by the critics as indulgent and self-deluded. Whilst we may applaud Angel for desiring a better life, and moving beyond her difficult childhood, the manner in which she does so give us pause to consider the way in which delusion can lead us into decline both physically and emotionally. Angel is a woman born out of time; Taylor suggesting, perhaps, that if she had been a post-war writer she may have had a different outcome. Angel’s agency thus becomes a tragic parody of empowerment, maintained through delusion.

Rumer Godden’s In This House of Brede (1969) is rather different. Philippa Talbot, a successful and sophisticated woman in her 40s, leaves behind a high-powered career in the British civil service to join a Benedictine monastery – Brede Abbey – in rural Sussex, although based upon Godden’s long-time engagement with Stanbrook Abbey in Worcestershire. At first glance, the monastic setting seems to erase worldly notions of power, the nuns renouncing personal ambition, sexual identity, and individual possession. However, Godden reveals the Abbey as a space in which hierarchies are as prevalent as they are in the outside world with power being reframed as both responsibility and service. The nuns’ communal decision-making processes, and their clear emotional intelligence, highlight alternative models of female agency whilst their internal rivalries and the demands of obedience present ongoing challenges. Godden also subtly critiques the limits imposed on even the most competent women in male-dominated religious institutions. Despite the novel’s idealisation of vocation, Philippa’s narrative is ultimately about reconciling personal autonomy with collective identity – a balance that defines post-war female experience.

Perhaps the best-known work included here, Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber (1979)stories, was the first of a number of second-wave feminist re-writings, or revisionings, of the fairy tale genre. Unlike the two ‘domesticated’ novels above, these short stories range from a reconfiguration of the tales of Bluebeard, Red Riding Hood, Beauty and the Beast and Snow White to a female vampiric tale that is resonant of Sheridan Le Fanu’s ‘Carmilla’, The Lady of the House of Love. In stark contrast to Taylor or Godden, Carter employs fantasy and pastiche to explore sexuality, violence, and liberation. Through all the fables, Carter consistently highlights that female power lies not in moral purity (whatever that may mean in 1979, and how we might read that today) but in becoming a self-aware and autonomous individual. Carter’s work arrived at the moment in which second-wave feminism had arguably reached its zenith, and builds on her earlier work in The Magic Toyshop (1967) and The Passion of New Eve (1977). Her heroines reclaim control of their environment, often through subversion or metamorphosis. Where Taylor’s Angel constructs fantasy to escape powerlessness, Carter’s women weaponise myth to expose and disrupt oppressive structures.

Alice Thomas Ellis’s The Birds of the Air (1980) has a number of factors in common with Godden’s work. A tightly woven novel with six central characters, and set over the Christmas period following the death of the daughter, Robin, which occurs prior to the novel opening, it explores grief, family dynamics, and spiritual confusion. The central characters – particularly Mary, the dead girl’s sister – are emotionally repressed and constrained by politeness, convention, and unspoken trauma and whilst Ellis’s characters rarely act decisively, and agency is often expressed through absence, withdrawal, or passive-aggressive hostility. However, beneath the surface, Ellis suggests that even minimal forms of dissent – sarcasm, estrangement, refusal to conform – carry a quiet form of mental agency. The surviving women, although numbed by loss and male-dominated social expectation, survive through detachment, dark humour, and Christmas ritual. Ellis critiques the emotional stoicism expected of women during this period, revealing how repression becomes both a burden and a survival strategy. Agency here is not triumphant, but it is not absent either – it resides in endurance and subtle resistance. There are elements of farce here, too, and Ellis’s use of the comedic highlights not only the boorishness of male behaviour, but the ways in which some female characters are yet to emerge from its shadow.

The course concludes with Anita Brookner’s Booker Prize-winning Hotel du Lac (1984). On first reading a book concerned with a form of quietism, we again have a novelist as our central character: Edith Hope. Having left England under a cloud – the details of which we are gently introduced to at various stages in the novel – Edith gradually begins to assert herself at the Hotel du Lac in Switzerland to which she has been guided (banished?) after deciding not to go through with her impending wedding due to still being in love with her married partner. Like Angel, Edith writes sentimental fiction; unlike Angel, she is self-aware, ironic, and resigned to her status as an outsider. At the hotel we meet a variety of other female guests, against whom Edith navigates her way toward reimagining her future, mentally forging a new path for herself whilst keeping her novel writing ongoing. Breaking free of the constraints of her emotional entanglements whilst looking toward a future in which she is free to act as she chooses, Edith is presented with another dilemma from a guest who may not be all that he seems. It is to her credit that Edith navigates this new challenge to her autonomy and Hotel du Lac, like The Birds of the Air before it, concludes with a sense of a fresh extra-textual life for her – one where she will decide her own future.

Power and agency in post-war women’s fiction are rarely straightforward. Across these five key works, female protagonists navigate limited choices, social constraints, and internal conflicts in pursuit of agency and power. Elizabeth Taylor’s Angel critiques ego yet celebrates autonomy and sheer bloody-mindedness. Rumer Godden’s In This House of Brede asks us to consider what role communal life may play in a fractured society. Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamberrejects patriarchal myth-making through reimagined fairytale. Alice Thomas Ellis’s The Birds of the Air promotes agency found in the virtue of derision; and Anita Brookner’s Hotel du Lacaffirms individual power outside of heterosexual relationships. Together, these novels map out different forms of post-war womanhood, overshadowed by tradition, perhaps, yet reaching – sometimes desperately, sometimes gracefully – toward real self-sufficiency and power. Whether through fantasy, religion, irony, or restraint, our authors expand the literary imagination of what female power can look like: contradictory, ambivalent, and deeply human.

Women and Power in Twentieth-Century Fiction: 1950s-1980s, with Miles Leeson. Live online course of lectures and seminars. Sundays, fortnightly, 14 September to 9 November 2025, 6.00-8.00 pm British Time.