The Bloomsbury Group: Who were they?

Who were the Bloomsbury Group?

Victoria Rosner writes:

Vanessa Bell, 1931

More than one hundred years have passed since the Bloomsbury Group met in a drawing room in a then-unfashionable London neighborhood, and the influence of its members is arguably more pervasive than ever. The economic theories of Maynard Keynes are debated in newspapers around the world. The novels of Virginia Woolf figure prominently on college syllabi. The homes and haunts of Bloomsbury receive thousands of pilgrims a year.

Adored by some and derided by others, the Bloomsbury Group remains, as it has always been, dificult to ignore. As the novelist E. M. Forster had it, ‘No civilization or attempt at civilization has succeeded Bloomsbury.’

There can be no doubt that the Bloomsbury Group continues to resonate today and that its legacy is still evolving. It might well be said that no other English-speaking gathering of friends in the past two hundred years has achieved such prominence or exerted such sway. This outsize influence derives in part from the range of the group’s endeavors: from paintings to politics, finance to fiction, design to dance.

While there is no unified Bloomsbury philosophy, the group was bound together both by lifelong ties of affection and by shared ideas about aesthetics, philosophy, and psychology. In our age of specialization, Bloomsbury’s willingness to integrate ideas from outside their individual specializations is a signal reminder of the benefits that can accrue to the omnivorous intellect.

The Bloomsbury Group was an intellectual and social coterie of British writers, painters, critics, and an economist who were at the height of their powers during the interwar period. The boundaries of the group were loose and fluid, though any membership roster would need to include Clive Bell, Vanessa Bell, E. M. Forster, Roger Fry, Duncan Grant, Maynard Keynes, Desmond MacCarthy, Molly MacCarthy, Saxon Sydney-Turner, Lytton Strachey, Adrian Stephen, Thoby Stephen, Leonard Woolf, and Virginia Woolf. Other key associates were Dora Carrington, David Garnett, Lydia Lopokova, Ottoline Morrell, and Vita Sackville-West.

Source: Victoria Rosner, Introduction to The Cambridge Companion to the Bloomsbury Group (CUP, 2014), pp. 2-3

*

The origins of the group lay at Trinity College, Cambridge University, where Thoby Stephen, son of the Dictionary of National Biography editor Leslie Stephen, set off to [university] in 1899, leaving behind his sisters, Vanessa and Virginia (formal higher education was unusual for women at the time). At Cambridge, Thoby fell in with a set of friends, most of whom were or would become members of the Cambridge Apostles, a discussion society for undergraduates. After leaving [Cambridge], to recapture the pleasures of those exchanges, he invited his friends to visit his home on Thursday nights to keep the conversations going. (Rosner, p. 3)

What, if anything, was so special about early Bloomsbury’s Thursday nights? For intelligent and articulate young women like the Stephen sisters, who had been educated exclusively at home, the experience of intellectual debate must have been a revelation. To be able to mull over ideas, freely and without much regard for propriety, was a new experience for all those who took part. Moreover, the ideas that were hashed out in Gordon Square became, for many of those in attendance, the basis for future independent work. The pleasures of the party were such that the conversation, in various configurations, lasted lifetimes and helped to spawn a great deal of influential and well-regarded intellectual work. Certainly we would not be looking back to Thoby’s Thursdays nights if it were not for their sequelae, the fruitful creative harvest of the Bloomsbury Group.

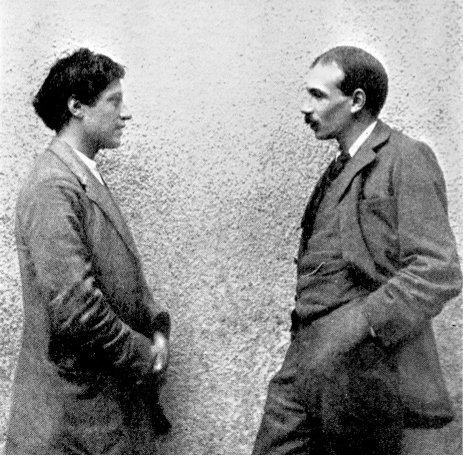

Duncan Grant and John Maynard Keynes

It would be wrong to give the impression that Thursday night talks focused exclusively on ethereal questions of philosophy; as often as not the discussion was decidedly earthy, and when it was, it was perhaps even more revelatory. In an age when relations between the sexes were far more constrained and homosexuality was punishable by imprisonment and forced labor, circumspection about one’s private life was the rule. The year 1905, when the Gordon Square evenings began, was only five years after the death of Oscar Wilde following his imprisonment under the Labouchere Amendment, which famously outlawed ‘gross indecency’ between men.

But at Gordon Square this taboo, too, was breached, and sex was as available for discussion as anything else. Bloomsbury practiced what it preached, too: free love, same-sex sexuality, and acceptance of all kinds of unconventional relationships. (Rosner, p. 5)

Our courses on Bloomsbury: Life and Writing ran weekly for six weeks in 2022. Our second Bloomsbury course, Art and Politics, runs March to April 2023.

Roger Fry, portrait of E. M. Forster