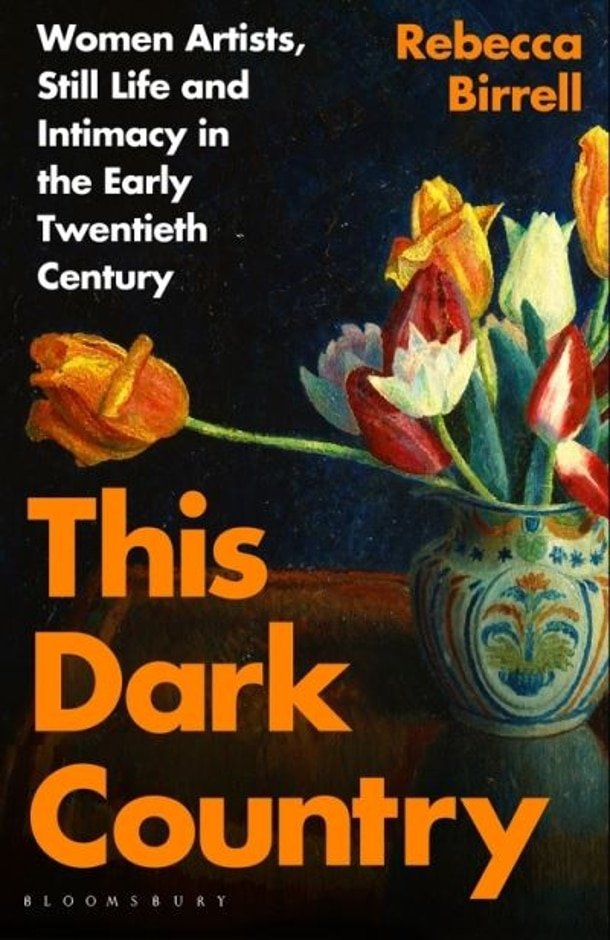

This Dark Country

Mitchell Alcrim reviews

This Dark Country by Rebecca Birrell (Bloomsbury, 2021)

In her essay, ‘Women and Fiction’ (1929), Virginia Woolf writes that: ‘Often nothing tangible remains of a woman’s day,’ and goes on to say that: ‘Her life has an anonymous character which is baffling and puzzling in the extreme.’ ‘[T]his dark country,’ she says, is a new area for exploration in fiction.

In This Dark Country: Women Artists, Still Life and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century, Rebecca Birrell shines a light on several early twentieth-century women artists and describes how they redefined notions of domesticity and intimacy in their lives and work. Some are well known, including Dora Carrington, Ethel Sands, Gluck, Vanessa Bell, Gwen John, and Nina Hamnet, while others, such as Edna Waugh, Mary Constance Lloyd, Winifred Gill, and Helen Coombe (all discussed in brief, but brilliant chapters) have nearly vanished from history.

All, Birrell tells us, were committed to ‘living awry to heteronormativity in some key sense, redefining what it was as a woman to experience love, friendship, coupledom and the family, and dedicating their lives to other women or to queer men.’ (Birrell, 4) All were also keenly attuned to the unique emotional power of still-life painting. (2) Moving beyond surface representation, Birrell discovers in these works ‘histories of women’s lives compiled by way of the objects that bore witness,’ (3) and unearths ‘densely coded dramas on the trials of intimacy and of needs hungering at the seams of quotidian concerns.’ (4) ‘[I]nterested more in possibility than proof,’ (15) Birrell experiences these paintings as ‘mediums for thought that invited [her] to think and feel with them.’

Birrell skillfully includes the reader in these experiences. Carrington’s painting, The Mill at Tidmarsh, described as ‘an exploration of [still-life’s] charged threshold,’ attains a striking immediacy as Birrell invites us to: ‘Begin where Carrington did’ and ‘to observe [her] as she contemplates the promise of that world … the moment before her acceptance by and passionate interest in the home commenced.’ (45-46) This is the home she shared with her companion, the gay writer Lytton Strachey. Here, Carrington created a new physical and emotional space where both her art and love for Lytton could flourish, not subject to the middle-class norms of her upbringing.

At Charleston, meanwhile, Vanessa Bell reimagined the possibilities of domestic bliss in her own way. Sharing a home and life with the gay artist, Duncan Grant, Bell created a domestic space that was ‘a living canvas.’ She and Grant collaborated in the redecoration of the entire house ‘with domestic life and radical aesthetics forever intermingling and bolstering one another.’ (224) At Charleston, artistic innovation and a new way of living supported and nourished each other, and not only for Bell and Grant. Charleston also offered a refuge for many friends in their circle. Birrell observes that at Charleston: ‘They need not hide here: this is what these stylistic decisions meant; they were free simply to be themselves.’ (224) In Grant’s interior scene of 1918, Bell is shown painting a still-life. The aesthetic questions which occupy her as she works are the same, in Birrell’s imagining, as those she pondered as she created a life outside societal norms: how will she reimagine the domestic? what will she retain or discard? how will Duncan be involved? We are told to ‘watch as the brush continues to move across the canvas.’ (188-189) It is this pervading sense of immediacy, indeed intimacy (only first names are used throughout, with the notable exception of Carrington, who chose to be called by her surname), that makes the book such a pleasure to read.

Ethel Sands’ home that she shared with her partner, Nan Hudson, for decades offers fertile ground for a recontextualisation of lesbian relationships. Sands’ elegant drawing-room interiors extract lesbianism from its conventional late Victorian associations with degradation and criminality, connecting it instead to sophistication and refinement. (105) Dismissed due to her prim appearance as poor wife material, Sands discovered the covert pleasures of a life when no one is looking. (116) Hiding in plain sight, Sands took labels such as ‘spinster’ and ‘virgin’ as ‘indicating a complete ignorance of the experiences she shared with the woman she loved.’ (101) Birrell tells us that: ‘To be dismissed by society as chaste, prim and unattractive was to bypass an unwanted life, and to settle into a queer one.’ (102) Sands, like many of the other women featured in Birrell’s book, discovered the benefits of a self-regulated invisibility which freed them to live and create as they chose. At the closing of the brief chapter on the largely forgotten artist, Mary Constance Lloyd, Birrell abandons the slim archive available to her, and writes compassionately of Lloyd that:

There was freedom in existing as she did, as a series of charged impressions, connected only to a handful of letters and finished artworks, sometimes as Mary and sometimes as Constance … I learnt to let her slip away unnoticed. (133)

Meanwhile, Gluck’s paintings of flawless flowers in works such as Chromatic, 1932, resist the narrative arc of heteronormative life and celebrate the boundless possibilities of queer lives. Gluck removes the spectre of death which traditionally haunts floral compositions. The association with the memento mori and inevitable death is absent. Aesthetic subversion points to a personal subversive claim. These flowers will not die; at a remove from biological processes, they are exempt from the usual cycles of maturation, reproduction and death. Similarly, Birrell suggests, queer lives are not subject to the script of courtship, marriage, and children. In Chromatic, in particular, Gluck signals an opportunity for possibility and invention in the lives of those who choose to live outside the confines of heteronormativity and its associated milestones; queer lives possess their own markers of success. (155) Elsewhere, in Lords and Ladies, the gender nonconforming Gluck questions the very nature of gender as natural, as anatomy as destiny. The asymmetries depicted in these flowers leave room for deviation, difference, and surprise. (161)

Improvisation and inventiveness were crucial in living these unscripted lives. For some, such as Gwen John and Nina Hamnett, rented rooms provided a space in which to experiment and innovate in art and life. These rooms offered an alternative to the confines of the conventional family unit and a space where female friendship could thrive. As Birrell writes, ‘The room was about understanding yourself – your creative aspirations, sexual desires and much else – as worthy of a discrete space.’ (267) Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own immediately springs to mind. In Gwen John’s many paintings of her rooms, she conveys the joys of living alone, ‘the pleasures of a spatial independence that was profoundly psychological in its effects.’ (267) Often extremely subtle changes can be observed in otherwise identical interiors, ‘suggesting that the self can transform while largely resembling what it once was, and we must notice, attend to and celebrate these shifts, however small, or lacking in legibility to others.’ (263) Birrell suggests that: ‘For Gwen, these rooms and their repetitions were assertions of presence: here I am … I survive, I go on living.’ For Nina Hamnett, who spent an entire lifetime in rented rooms, her still-lifes were a recording of this itinerant life, comparable, as Birrell writes, to the packing and unpacking of her belongings as she moved from lodging to lodging. (296) Uncertainty and ephemerality are harbingers of freedom, ‘unexpected intimacies’ (298) and personal choice. Elsewhere, in her portraits of landladies, ‘a different kind of woman emerges’, Birrell tells us, ‘unattached and unneeded … a woman who renounces nothing that gives her pleasure.’ (322)

In her introduction, Birrell writes, ‘I learnt to put my trust in the alternative path they charted: speculation, fantasy, hope, empathy – emotional experiences united by possibility.’ (14) Throughout this fascinating book, it is this notion of imaginative possibility which lingers. At the close of her chapter on Carrington, Birrell figures an alternative ending for her, escaping her status as tragic figure:

Imagine her always in motion, on horseback, under a mantle of darkness, moving towards an ending which was as yet undetermined.

Birrell leaves us with Carrington triumphing over posterity, the author of her own destiny. It is this sensitivity and compassion which are the hallmarks of This Dark Country. In celebrating these remarkable women’s immense capacity for new ways of being and feeling, Birrell grants them their rightful place in early twentieth-century cultural history while offering us the chance to engage new methods of seeing and thinking about women’s lives and art.

Mitchell Alcrim, Cambridge, Mass.

Links

The Garden Museum has some wonderful Gluck paintings on its website.

Tate Gallery London on Dora Carrington.

National Portrait Gallery London on Vanessa Bell.

Frances Spalding biography of Vanessa Bell.