Book Review: New edition of Woolf's Diary

It Loosens the Ligaments’: A Review of Virginia Woolf’s ‘Unexpurgated’ Diary

The Diary of Virginia Woolf, volumes 1-5, by Virginia Woolf (Granta Books, 2023)

Review by Dr Galen Bunting, Northeastern University, Boston, Mass.

The topmost level of my undergraduate university library was lined with tall pine bookshelves, where I found The Diary of Virginia Woolf in five volumes (1977-1984). Edited by Anne Olivier Bell, wife of Woolf’s nephew, Quentin Bell, this was the most complete version of Woolf’s diaries. My university library eventually recalled the books, and since the diaries were out of print, I found them difficult to locate indeed.

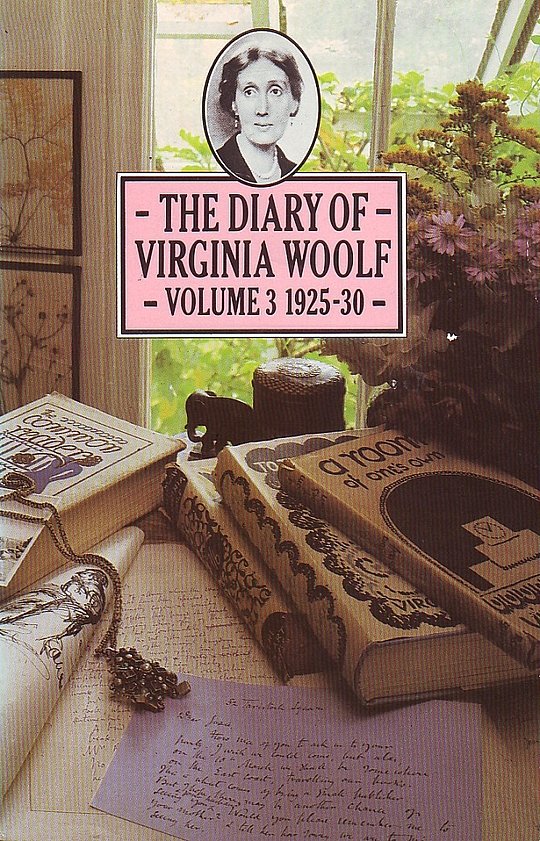

The new Granta edition of Woolf’s Diary, vol. 2

From 1915 onwards, Virginia Woolf maintained a continuous diary across thirty separate books. Anne Olivier Bell transcribed these diaries alongside the abridged transcription prepared by Kathleen Wilson for Leonard Woolf (which would be published in 1955 as A Writer’s Diary). This process took twenty years to accomplish. Woolf’s diaries are now available in a new edition from Granta, which preserves Bell’s editing while restoring passages which were originally omitted. For readers of this new edition, Virginia Woolf’s diaries offer an immense gift to the literary world.

As her daughter Virginia Nicolson recalls in a new forward, Bell’s watchwords were ‘ACCURACY/RELEVANCE/CONCISION/INTEREST’, pinned above her editor’s table as she worked (viii). In this version, Anne Olivier Bell thought it prudent to leave out ‘passages which might have caused distress or offence’ (viii). Granta’s new edition has reinstated these ‘omitted sections’, presenting eager readers with Woolf’s journals ‘in full, unexpurgated’ (viii).

From 1915 to 1941, Woolf’s diary was a place in which she wrote character sketches of her friends, acquaintances, and enemies – and riffed on their foibles. Woolf carefully recorded her reading as she prepared to write reviews and essays. Editor Matthew Holliday includes Woolf’s 1917 Asheham diary, which offers a view into her inner life during the First World War. Sadly, Woolf’s journals from 1897 to 1909 are omitted, but can be consulted in an edition published in 1990 under the title A Passionate Apprentice. Each volume covers a particular span of years, and they feature new forwards by Virginia Nicolson (Volume 1: 1915-1919), Adam Phillips (Volume 2: 1920-1924), Olivia Laing (Volume 3: 1925-1930), Margo Jefferson (Volume 4: 1931-1935), and Siri Hustvedt (Volume 5: 1936-1941).

The first volume begins as Woolf resolves to keep a diary for 1915. In her second full diary entry, dated Saturday 2 January 1915, Virginia Woolf describes that she has written ‘about 4 pages of poor Effie’s story’ (5). ‘Effie’ would later be renamed Katharine, the heroine of Night and Day (1919), Woolf’s first commercially successful novel. Across Woolf’s daily reflections, her writing is not separated from her life, nor are her reading habits.

Adam Phillips explains that, ‘the diaries, more starkly than her fiction, track her craving for connection and affection, closeness and intimacy, always contending with her despair about whether such things were possible or viable’ (vol. 2, xi). After she describes the selection and purchasing of Monks House in Lewes, Woolf writes on 12 July 1919:

In public affairs, I see I’ve forgotten to say that peace was signed; perhaps that ceremony was accomplished while we were at Asheham. I’ve forgotten the account I was going to write out of the gradual disappearance of things from shop windows; & the gradual, but still only partial reappearance of things. Sugar cakes, currant buns, & mounds of sweets. The effect of the war would be worth describing, & one of these days at Monks House – but why do I let myself imagine spaces of leisure at Monks House? I know I shall have books that must be read there too, just as here & now I should be reading Herman Melville, & Thomas Hardy, not to say Sophocles, if I’m to finish the Ajax, as I wager myself to do, before August. But this dressing up of the future is one of the chief sources of our happiness, I believe. There’s still a good deal of the immediate past asserting its claim on me. I met Morgan Forster on the platform at Waterloo yesterday; a man physically resembling a blue butterfly– I mean by that to describe his transparency & lightness (vol. 1, 375).

In this passage, we see Woolf at her best: her writing, reading, and relationships, as well as her experiences during both world wars, are all caught up in her descriptions of her friends.

On 22 July 1926, Woolf writes, ‘I drive my pen through de Quincey of a morning, having put The Lighthouse aside till Rodmell” (vol. 3, 118). Woolf goes from drafting To the Lighthouse to reading Thomas de Quincey’s Suspiria de Profundis (1845), a collection of surreal psychological essays in which de Quincey depicts the process of memory as affected by opium. This reading provides a means of inspiration, which Woolf presages in her diary. On Saturday 31 July 1926, Woolf writes out a sketch of ‘My own Brain’, after the method of de Quincey, as she documents her experience of ‘a whole nervous breakdown in miniature’, which manifests in a ‘tasteless, colourless’ world, and deep fatigue (vol. 3, 128).

Woolf’s decision to describe the aftermath of a breakdown may have been inspired by her reading of de Quincey: she pictures herself as a one-dimensional fictional character, as ‘Character & idiosyncracy as Virginia Woolf completely sunk out’ (128).

Enormous desire for rest. Wednesday – only wish to be alone in the open air. Air delicious – avoided speech; could not read. Thought of my own power of writing with veneration, as of something incredible, belonging to someone else; never again to be enjoyed by me. Mind a blank. Slept in my chair (128).

When her period of mental collapse is easing, Woolf charts her own mental recovery through reading: ‘Curiosity about literature returning: want to read Dante, Havelock Ellis, & Berlioz autobiography…’ (128). Woolf’s diary offers a form of mental rehearsal, as she irons out her process of writing, reading, and reasoning.

Woolf scholars may well be wondering, what differs in Granta’s edition – that is, what qualifies as unexpurgated? In the front matter, an editorial note reads: ‘The language used and/or views expressed in the diary of Virginia Woolf and the original editorial material are those of the respective authors in their time and do not represent the publisher’s attitudes.’ From this early diary to her last, Woolf’s frank thoughts have been restored by Matthew Holliday. As Alison Light shows us in Mrs Woolf and the Servants, while Woolf was a progressive, her relationship with domestic laborers was an embattled one: ‘Virginia’s public sympathy with the lives of poor women was always at odds with private recoil’ (203). In an entry dated 13 December 1917, Woolf reflects, ‘The poor have no chance; no manners or self control to protect themselves with; we have a monopoly of all the generous feeling’ (Vol. 1, 114). Olivia Laing characterises Woolf as ‘at her least appealing in the fifty-three entries documenting her struggles with her cook, Nellie Boxall’ (x). Throughout her diaries, ‘Woolf was capable of shocking episodes of snobbery and cruelty’ (x).

But Woolf also reveals ‘intimate, piercing, gossipy, voracious, dreamy, amused, deprecating’ intimations of great ‘sensitivity’. (x). As Laing describes, Woolf sought to depict a full picture of her daily life in frank detail: ‘There are the great set-piece scenes, like meeting Thomas Hardy or the total eclipse of 1927, but you can also trust her to tell you that the newly installed loo doesn’t flush’ (Vol. 3, x). In these unexpurgated diaries, Woolf writes as a form of self-therapy: as she reflects on September 5, 1927, ‘to soothe these whirlpools, I write here’ (196).

Woolf’s Diary was first published by Penguin in 5 volumes in the 1970s and is much used by scholars.

Woolf’s diary proves a form of literary exercise, which she compares to calisthenics: ‘The habit of writing thus for my own eye only is good practice. It loosens the ligaments. Never mind the misses & the stumbles’ (342). In Appendix 3 of the first volume, Woolf’s Asheham diary has been included. A slim book, Woolf’s observations of the First World War from Asheham House in the Sussex countryside are staccato, yet ever-present. On 20 April 1917, ‘12 aeroplanes in order went over us after tea. Tortoiseshell butterflies out. We went to Lewes’ (429). Woolf’s own journey appears alongside the procession of butterflies, as though the aeroplanes are perhaps part of the same convoy. Woolf’s observations of the war eerily anticipate Mrs Dalloway, as she pairs a flight of aeroplanes with observations of the natural world, which echo the scene in the novel when a sky-writing aeroplane crosses the tree-lined sky of Regent’s Park. In Woolf’s war diary, meeting German prisoners and mushroom hunting are juxtaposed, as she relates on 26 August:

Very windy, sunny at times, but unsettled. Met Gunn getting his harvest in with German prisoners. To get papers, but they were not sent. Home over the top. A great many blackberries. Saw no mushrooms (436).

Throughout Woolf’s Asheham diary, the war is nearly mundane, its presence a constant element in daily life.

Woolf’s last journal entry is dated 24 March 1941, three days before she drowned herself in the River Ouse. Her last words trail off with an ellipsis: ‘L. is doing the rhododendrons . . .’ (478). L. is Leonard, and the rhododendrons are in the garden at Monks House, where she wrote Between the Acts, which would be published after her death. In this final entry, Woolf presents nature alongside her relationships with other people, the very insights which still infuse her writing with candor and vivid power to this day.

In his introduction to the original first volume of Virginia Woolf’s diary, her nephew, artist Quentin Bell, suggests, ‘When, therefore, the last of these volumes comes from the press, the œuvre of Virginia Woolf will be complete and the critics may, if they so wish, sit down and assess it as a whole’ (xxi). Including new forwards, Woolf’s 1917 Asheham diary, appendices, and indices, the complete and definitive edition of Woolf’s diaries is now available from Granta Books in five volumes. In its pages, scholars, students, and admirers of Virginia Woolf’s writing can experience her diaries in their most complete form.

Works Cited

Alison Light, Mrs Woolf and the Servants: An Intimate History of Domestic Life in Bloomsbury (Bloomsbury Press, 2009)

Virginia Woolf, The Diary of Virginia Woolf, volumes 1-5 (Granta Books, 2023)