On Andrew Pham, Twilight Territory

On Surviving History

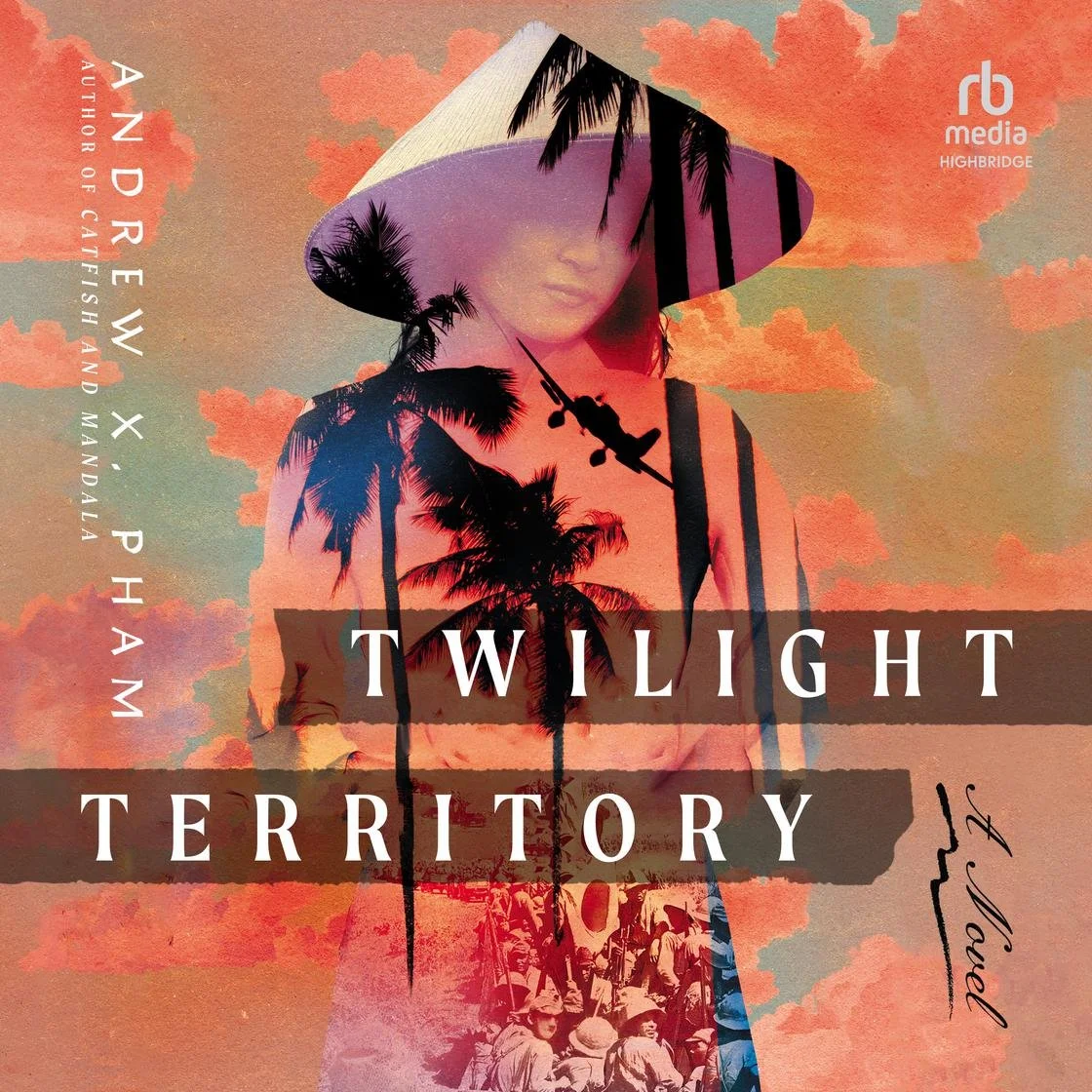

Review of Andrew X. Pham, Twilight Territory (W. W. Norton, 2024)

Before he died in April 2025, the celebrated Vietnamese American author Andrew X. Pham bequeathed a final book to the world. Pham’s earlier works of nonfiction have garnered widespread praise for their originality and lyricism, earning him such honours as the Kiriyama Prize, the Whiting Writers’ Award, and a Guggenheim fellowship. Twilight Territory is his first novel, but it explores the same themes that preoccupied him for his entire literary career: the history of the Vietnamese nation and people, the collision of ordinary lives with international upheavals, the search for home amidst the hardships of displacement. Pham powerfully developed these themes in Catfish and Mandala (1999), a memoir that remains one of the most important works ever written by a Vietnamese American author. In The Eaves of Heaven: A Life in Three Wars (2008), he wrote about his father’s experiences of the French and American wars in Viet Nam. Now, inspired by the life of his maternal grandmother, Pham recounts the fictional story of Tuyet, a Vietnamese single mother who falls in love with Takeshi, a major in the Imperial Japanese Army.

When they meet in 1942, both Tuyet and Takeshi are already displaced. He longs to return to Hokkaido, but is duty-bound to remain in Viet Nam. She is an orphan removed from her birthplace, impoverished and ostracised after her divorce. Despite the risks of courting across colonial lines, the two eventually discover their deep commonality:

Long years of sorrow and isolation had prepared Tuyet. Her heart turned toward him. He spoke a language she knew well, the language of loss and loneliness. From her earliest memory, Tuyet knew what it was to be without family. She was unaware that she suffered the universal hunger of orphans, a profound yearning to be loved, to be wanted. It rendered her vulnerable. (Twilight Territory, 70)

A sense of foreboding pervades the pair’s courtship and eventual marriage. Around them, the battle for Viet Nam rages.The destinies of French colonialists, Japanese military officials, and Vietnamese peasants intermingle during the turbulent latter half of the Second World War. In Viet Nam, the conflict resulted in famine, the entrenchment of a stifling French regime, and the rise of the guerrilla resistance movement known as the Viet Minh. Takeshi defects from the defeated Japanese army and joins the growing Vietnamese independence movement. The pair live in flight. Takeshi later confesses to Tuyet,

‘I thought you would resent me for this hard life.’ They lay on their sides facing each other. She ground her knuckles into his palm, like mortar and pestle. With a little shrug, she said, ‘You have not broken my heart. I have no reason to resent you. A hard or an easy life, that’s destiny.’ (197)

In times of chaos and brutality, many of Pham’s characters, Takeshi included, survive by being ruthless and resourceful. Tuyet, however, maintains her dignity through her acceptance of her fate and love for her people.

Sympathetic portrayals of individuals on opposing sides of war – their options, their motives, their regrets – is a hallmark of Pham’s writing. This leitmotif returns in Twilight Territory, both in Tuyet and Takeshi’s relationship and in the novel’s broader narration of the rise of the Viet Minh. The Viet Minh would eventually gain control of North Vietnam and, after evolving into the Communist Party of Viet Nam, defeat the South Vietnamese-American alliance in the American-Vietnamese War (known in many Western nations as the ‘Vietnam War’, 1965–1975). Pham, a South Vietnamese, fled Viet Nam with his family in 1978 to escape this victorious Communist regime, although not before his father was interned in one of their notorious re-education camps. But in Twilight Territory, Pham depicts the desperate conditions that led many Vietnamese to join the Viet Minh resistance in the mid-twentieth century and fight for independence against a long line of foreign occupiers. Nothing is straightforward in Viet Nam’s history of war, and Pham renders the choices of people caught in the crossfire of conflict with remarkable compassion.

While the subject matter is fresh and the historical perspective interesting, in shifting from memoir to historical fiction Pham at times exchanges the most luminous aspects of his prose – dazzling descriptions of food and landscapes; complex characters achingly drawn from his past; penetrating reflections on history’s small and great tragedies – for action sequences and occasionally-stilted dialogue. Still, Pham possesses an intimate understanding of the spiritual searcher, and his narration of Tuyet’s journey is effectively delivered and hauntingly concluded. Readers familiar with Pham’s earlier work will note the return of significant locations, such as the fishing village of Phan Thiet where Pham was born and the beach at Mui Ne from which the Pham family fled Viet Nam by boat. Twilight Territory’s final scene in particular offers a powerful counterpoint to the conclusion of Catfish and Mandala. Viewed in this light, Twilight Territory reads like the last instalment in a spiritual geography of Viet Nam that encompasses three generations.

Although I felt that the prose of Twilight Territory did not quite attain the soaring heights of Pham’s other works, it succeeds as a lush love letter to Viet Nam. Vietnamese people, landscapes, culture, and history are richly rendered on every page. Some of Pham’s finest descriptive passages appear in this novel. Take the following as one example:

A violet haze filled the predawn sky. Major Yamakazi’s black sedan swung into the main road, followed by a jeep and a covered truck with a squad of soldiers. Behind the convoy, a long hedge of fog-like dust hung in the still air. Muted shadows crept along the fields. The main highway, an obsidian marvel of colonial engineering, stretched straight through the sparsely inhabited country. Not a single motor vehicle in sight. Peasants were trekking into town on foot, bicycles, and oxen carts laden with corn, watermelons, and pineapples. Along the side of the road, women shouldered yoke-baskets full of produce, walking as though on invisible legs, their dark trousers melding seamlessly into the twilight, their bluish-white tunics floated ghost-like in the indigo air. They moved at a brisk pace, a cadence of steps matching the sway of their loads to ease the weight. All around, harvested paddies were dotted with scraggly clumps of trees and hardy palms. A low range of dark green mountains loomed far to the west. The fresh morning air was laced with a thread of brininess from the sea, hidden behind a low rise of land to the east. Closer to town, rows of shacks and bungalows lined the road. (38)

In moments like these, we gain a sense of just how close Pham has become with Viet Nam in the years since his first return, chronicled in Catfish and Mandala. He moved to live in the region some years ago. Although Pham’s writing has found a global audience, his work takes on special significance within the American literary context: he has undoubtedly succeeded in promoting a greater understanding of Viet Nam in its former enemy nation.

For all who have enjoyed Pham’s previous work, and for any readers interested in an eminently readable and humanising perspective on this lesser-known theatre of the Second World War, Twilight Territory will be a welcome new addition to the bookshelf. And for those who, like myself, regarded Pham as a dear literary friend, Twilight Territory will be cherished as a parting gift, his last offering to the literary world. It is a celebration of a career characterised by profound attention to the human element in any war and a deep empathy for the people – both combatants or civilians – whose lives become swept up in conflict, sometimes for no other reason than the fact of their birthplace.

Julie Wendel

McGill University, Canada

January 2026

Julie Wendel completed her MPhil at Cambridge University where she wrote a dissertation on Vietnamese refugee memoirs. Her current PhD research explores portrayals of refugees in twentieth-century fiction and reportage.

We also review The Eaves of Heaven by Andrew Pham.