Nature in the novels of Iris Murdoch

Miles Leeson offers some thoughts on the five books we will study in our new course,

Iris Murdoch and the Natural World

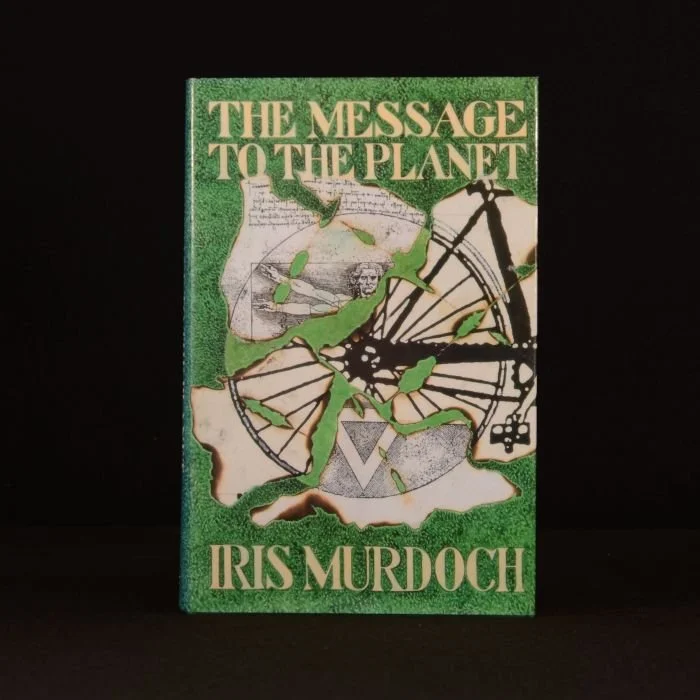

A vital but underappreciated element of Murdoch’s literary landscape is her treatment of the natural world. It functions not merely as a backdrop but as a transformative space that both sits apart from her characters and immerses them in her own form of reflexive realism. In all of her novels, but particularly in The Unicorn (1963), The Sea, The Sea (1978), Nuns and Soldiers (1980), The Good Apprentice (1985) and The Message to the Planet (1989), Murdoch engages with nature as both a physical reality and a symbolic force, intertwining it with her philosophical concerns about egoism, transcendence, and the pilgrimage toward ‘the Good’. This new course from Literature Cambridge will discuss these five novels in depth, and make reference to her other fictional, philosophical, theological and poetic work.

In The Unicorn nature is beautiful yet deadly. Set on the west coast of Ireland, the landscape is elemental and isolating: as Gerald Scottow tells us early on regarding the cliffs, ‘They are said to be sublime … again, I am no judge. I am too used to them.’ Marian Taylor arrives at Greytown junction to become the governess at Gaze Castle, where she finds a strange, stagnant dreamworld dominated by the mysterious figure of Hannah Crean-Smith. The natural world reflects the psychological and metaphysical imprisonment of the characters; the environment is not benevolent but mirrors the spiritual desolation of a place cut off from the possibility of transcendence or renewal. It is a rugged and untamed space – highlighted in the first few pages of the novel through Marian’s eyes, and her conversation with Gerald – and serves to emphasise the novel’s concern with failed transcendence and the perils of idealisation and isolation. The gothic nature of the landscape reminds us of Murdoch’s suspicion of romantic fantasy. Instead, she uses nature to question the possibility of freedom and escape within an environment corrupted by illusion and imprisonment.

The Sea, The Sea, which won the Booker Prize, turns to the marine landscape as both a literal and symbolic presence. The sea, surrounding Charles Arrowby’s coastal cottage, represents a sublime and unpredictable force that is, by turns, beautiful and terrifying – perhaps it even contains monsters. Charles has retreated to the coast (possibly based on Robin Hood’s Bay in North Yorkshire) to escape the entanglements of his former life as a theatre director and to pursue a delusional romantic ideal: the writing of his memoirs. However, his original ideal is thrown into chaos when he discovers his first love, Hartley, living in the nearby village. In the novel Murdoch presents the natural marine world as a moral and metaphysical mirror; Charles is constantly projecting onto it by interpreting its movements and moods in correspondence with his own internal states. Yet the sea resists such projections – it is indifferent, unlimited, and beyond his control. In one of the novel’s most dramatic scenes, Charles nearly drowns; a moment that reveals both the danger of the sea and the delusional nature of his self-image. The sea challenges his egoism and forces him to confront his fantasies. Unlike the closed, claustrophobic world of The Unicorn, nature has the capacity to jolt the self out of its illusions – but only if the self is willing to reflect and pay attention to reality. Murdoch’s use of the sea here (indeed in many of her novels) is as a force of awe, echoing her philosophical interest in the sublime as a way of decentering the ego and opening the self to moral reality.

Nuns and Soldiers takes place primarily in a more domestic and urban setting, split between London and the French countryside, yet nature again plays a critical role. Nature here is often aligned with the visual, especially through the perspective of Tim, whose painterly gaze tries to capture the fleeting beauty of landscapes and bodies. Murdoch uses this artistic engagement with nature to explore the moral dimensions of attention. As in her philosophy Murdoch sees the act of ‘unselfing’ – of attending to the world and others without the interference of ego – as the foundation of morality. In Nuns and Soldiers the countryside serves as a place of both relaxation and, later through a near-death experience (similar in tone to the near-death experiences in The Unicorn and The Sea), transformation. For Gertrude (who early on in the novel loses her husband) and Tim, it offers a temporary escape from social judgment and emotional complexity but also becomes a testing ground for their relationship. Murdoch uses the landscape of southern France, particularly mountains and rivers, to trace the development of emotional and moral clarity in her characters, whilst also drawing on the late work of Henry James.

Guilt rather than landscape initially dominates The Good Apprentice. The novel focuses on the young Edward Baltram who accidentally causes the death of his friend, Mark Wilsden, and subsequently spirals into guilt and remorse. Edward’s journey of redemption takes him to the countryside where he meets his estranged father, Jesse, and is drawn toward others struggling with their own psychological faults and failings. Nature in this novel is, by turns, pastoral and menacing, offering a contrast to the chaotic and morally ambiguous world of the London that Edward leaves behind him. His movement from urban London into the natural world reorients the narrative toward moral redemption and his time at Seegard, his father’s estate, is filled with symbolic natural imagery: the trees, gardens, animals, and the rhythms of natural life. These elements are not romanticised but serve as part of Murdoch’s ongoing philosophical exploration of how moral clarity often requires a confrontation with reality – with both the human and the ‘more-than-human’ world. Murdoch employs nature here in a way that aligns with her Platonic belief in the Good as something outside the self, something to be discovered through love and attention. Edward’s gradual awakening – his realisation that he must live not in fantasy but in imaginative service to others – is framed by the natural world’s quiet, persistent presence. The landscape at Seegard is not miraculous but it is patient and enduring, offering the possibility of re-orientating one’s inner life.

In The Message to the Planet nature appears as both a sublime force and as a context for philosophical reflection and potential moral regeneration through suffering. Marcus Vallar, a charismatic and enigmatic figure who is variously seen as a new-age guru, mathematical genius (this much is true), supernatural healer, and quasi-philosopher, is at the centre of events. His friend and acolyte Alfred Ludens believes that Vallar might possess a spiritual ‘message to the planet’ – a moral teaching that could save humanity. Vallar departs from his life in London to a rural cottage; his followers seek him out and find him living as a hermit. The landscapes are less dramatic than in The Sea, The Sea, but they serve as an essential space of healing and mystery. Nature here is associated with slowing down, listening, and coming to terms with finitude and the reality of others. However, Murdoch complicates any simplistic notion of nature as inherently redemptive through Vallar’s failure to provide a clear moral message, and his eventual descent into silence and ‘madness’ suggests that neither philosophy nor nature alone can offer salvation. What nature does in the novel – indeed in all of the novels highlighted here – is offer a space for moral confrontation. Nature is the essential medium through which the characters grapple with their own limits of understanding and redemptive suffering.

Within these five novels, Murdoch treats nature not simply as background scenery or as a space of dramatic ambiguity, but as an active participant in her moral psychology that fashions her fiction. By turns hostile, sublime, serene and ambiguous, the natural world in her fiction challenges her characters to move beyond egoistic fantasy and toward a fuller apprehension of reality – and of the moral imagination. Nature serves multiple purposes, reflecting back the moral failures and potential redemptions of the characters in question. Murdoch’s fictive natural worlds are never sentimental or romantic despite what the characters may perceive, but nor are they benevolent. In her philosophical work, to attend to nature is to practice a kind of moral seeing: to recognise the world as it is, not as one wishes it to be. This moral vision – drawn from her reflections on attention, indebted to Simone Weil – is at the heart of all of her work. Through The Unicorn, The Sea, The Sea, The Message to the Planet, Nuns and Soldiers, and The Good Apprentice, Murdoch reveals how nature shapes, reflects, and tests human character. Indeed, all of her characters approach the natural world in different ways, but those who are self-aware realise that they must not try and conquer the world but encounter it, resisting the urge to make it into their own private fantasy. In so doing they move slowly – inch by inch – toward the form of the Good that Murdoch urges us all to contemplate.

I hope you’ll join me on the journey.

Iris Murdoch and the Natural World: live online course with Miles Leeson, Director of the Iris Murdoch Research Centre.

Sundays, fortnightly, 15 March to 10 May 2026, 6.00 to 8.00 pm UK time.

Above: Wave photo by Tim Marshall, Unsplash.