Victorian Women: 5. Middlemarch

We study six great books by and about women in our Victorian Women course, live online, September to November 2023.

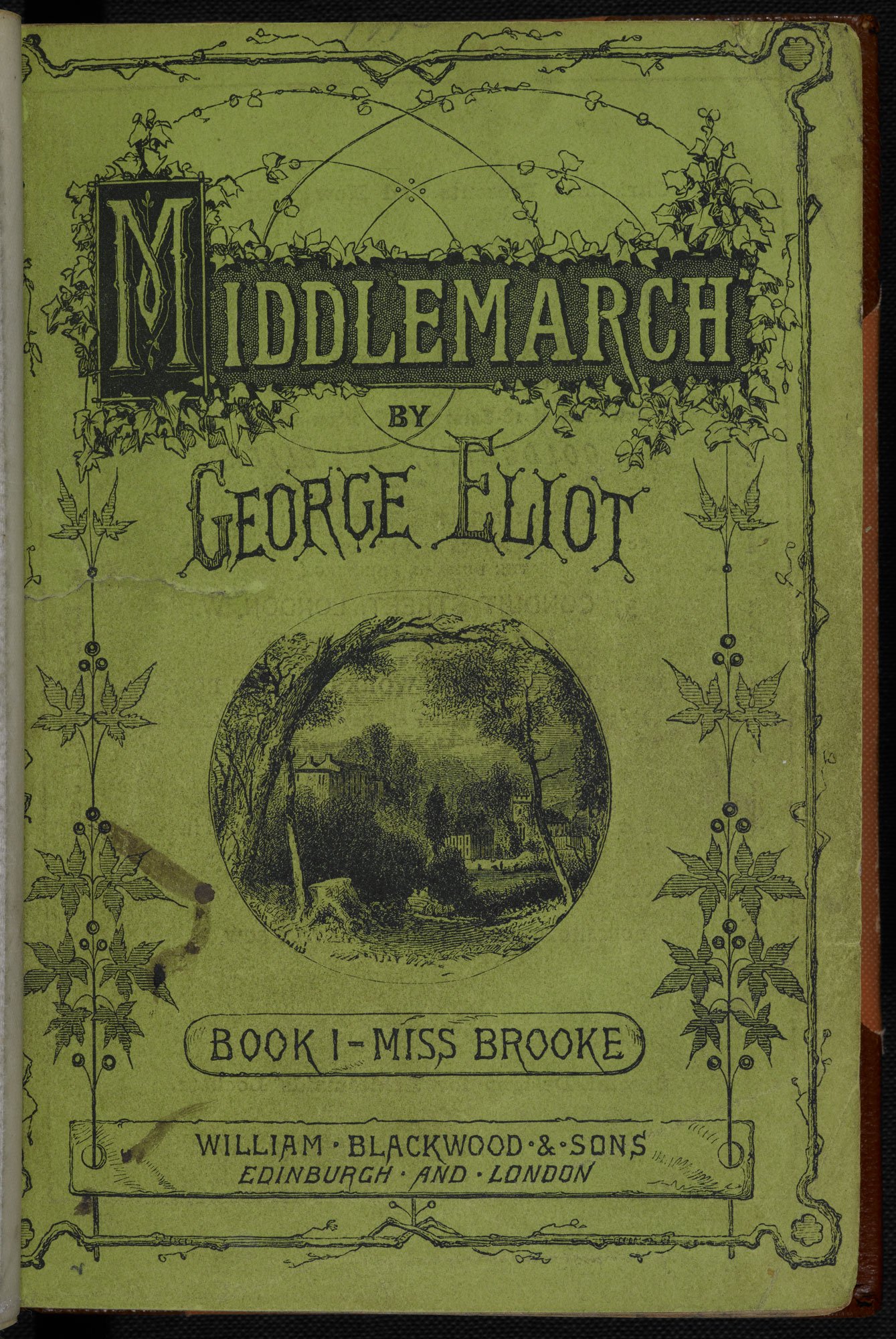

Lecturer Clare Walker-Gore reflects upon each of the books in a series of blog posts. Here she looks at George Eliot, MIddlemarch (1872)

From Middlemarch

Two hours later, Dorothea was seated in an inner room or boudoir of a handsome apartment in the Via Sistina.

I am sorry to add that she was sobbing bitterly, with such abandonment to this relief of an oppressed heart as a woman habitually controlled by pride on her own account and thoughtfulness for others will sometimes allow herself when she feels securely alone. And Mr. Casaubon was certain to remain away for some time at the Vatican.

Yet Dorothea had no distinctly shapen grievance that she could state even to herself; and in the midst of her confused thought and passion, the mental act that was struggling forth into clearness was a self-accusing cry that her feeling of desolation was the fault of her own spiritual poverty. […]

Not that this inward amazement of Dorothea’s was anything very exceptional: many souls in their young nudity are tumbled out among incongruities and left to ‘find their feet’ among them, while their elders go about their business. Nor can I suppose that when Mrs. Casaubon is discovered in a fit of weeping six weeks after her wedding, the situation will be regarded as tragic. Some discouragement, some faintness of heart at the new real future which replaces the imaginary, is not unusual, and we do not expect people to be deeply moved by what is not unusual. That element of tragedy which lies in the very fact of frequency, has not yet wrought itself into the coarse emotion of mankind; and perhaps our frames could hardly bear much of it. If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.

When we first meet young, marriageable Dorothea Brooke, heroine of Middlemarch, we are led to expect that her marriage will be one of the main concerns of the novel – and we have every reason to think that it will also end the novel, as the heroine’s marriage so often does. But Eliot deliberately confounds our expectations by marrying her off to someone quite obviously unsuitable by the end of the first of the novel’s eight books.

Here, less than a quarter of the way through the narrative, we are given our first glimpse of Dorothea after her marriage – already unhappy, and also, we might think, already having made the one choice that was hers to make. What happens to a heroine after marriage is a question that the marriage plot novel more often avoids than answers; vague mentions of marital bliss and specific mentions of children are usually all that we are afforded.

But here, Eliot draws back the curtain and invites the reader into an aspect of ‘ordinary human life’ which the marriage plot novel usually veils: the experience of a prosaically, undramatically unhappy marriage. Casaubon is no Percival Glyde; Dorothea is subjected to no obvious or outrageous cruelty. And yet the misery of their relationship is exquisitely painful to examine, precisely because it is so quotidian, so believable, and apparently beyond remedy. It is not, however, beyond the scope of the novel, and Eliot insists that we not only hear Dorothea’s secret sobs – part of ‘that roar which lies on the other side of silence’ – but that we consider what a heroine does after she has made her irrevocable choice, and found it to be the wrong one.

The Victorian Women course first ran in autumn 2022 and was repeated Sept.-Nov. 2023.

Dr Clare Walker Gore has taught at the Open University and the University of Cambridge. She is a Fellow of Lucy Cavendish College, University of Cambridge.