Poetry of the First World War

Below is a small selection of poems from the First World War. Links to further poems and archives are at the end of the page.

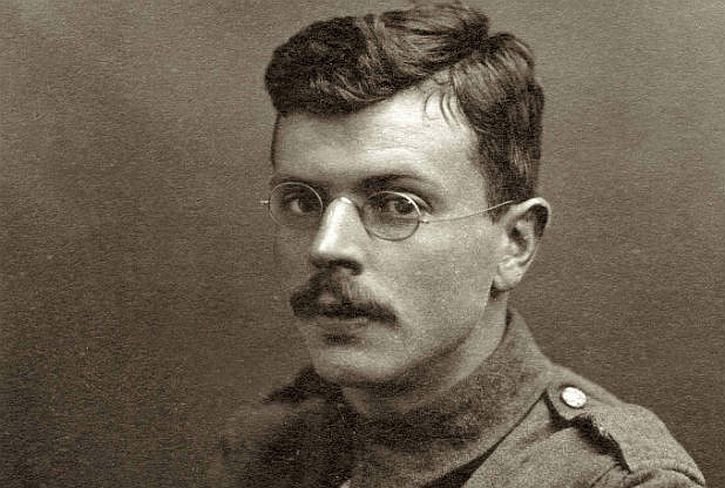

Ivor Gurney

Strange Service

Little did I dream, England, that you bore me

Under the Cotswold hills beside the water meadows,

To do you dreadful service, here, beyond your borders

And your enfolding seas.

I was a dreamer ever, and bound to your dear service,

Meditating deep, I thought on your secret beauty,

As through a child's face one may see the clear spirit

Miraculously shining.

Your hills not only hills, but friends of mine and kindly,

Your tiny knolls and orchards hidden beside the river

Muddy and strongly flowing, with shy and tiny streamlets

Safe in its bosom.

Now these are memories only, and your skies and rushy sky-pools

Fragile mirrors easily broken by moving airs ...

But deep in my heart for ever goes on your daily being,

And uses consecrate.

Think on me too, O Mother, who wrest my soul to serve you

In strange and fearful ways beyond your encircling waters;

None but you can know my heart, its tears and sacrifice;

None, but you, repay.

Ivor Gurney

The Stokes Gunners

When Fritz and we were nearly on friendly terms—

Of mornings, furtively, (O moral insects, O worms!)

A group of khaki people would saunter into

Our sector and plant a stove-pipe directed on to

Fritz trenches, insert black things, shaped like Ticklers jams—

The stove pipe hissed a hundred times and one might count to

A hundred damned unexpected explosions,

Which was all very well, but the group having finished performance

And hissed and whistled, would take their contrivance down to

Head quarters to report damage, and hand in forms

While the Gloucesters who desired peace or desired battle

Were left to pay the piper—Cursing Stokes to Hell, Montreal and Seattle.

(1925)

Ivor Gurney

Bach and the Sentry

Watching the dark my spirit rose in flood

On that most dearest Prelude of my delight.

The low-lying mist lifted its hood,

The October stars showed nobly in clear night.

When I return, and to real music-making,

And play that Prelude, how will it happen then?

Shall I feel as I felt, a sentry hardly waking,

With a dull sense of No Man's Land again?

Eleanor Farjeon

Now that you too must shortly go

Now that you too must shortly go the way

Which in these bloodshot years uncounted men

Have gone in vanishing armies day by day,

And in their numbers will not come again:

I must not strain the moments of our meeting

Striving for each look, each accent, not to miss,

Or question of our parting and our greeting,

Is this the last of all? is this—or this?

Last sight of all it may be with these eyes,

Last touch, last hearing, since eyes, hands, and ears,

Even serving love, are our mortalities,

And cling to what they own in mortal fears:—

But oh, let end what will, I hold you fast

By immortal love, which has no first or last.

Eleanor Farjeon

Peace

I.

I am as awful as my brother War,

I am the sudden silence after clamour.

I am the face that shows the seamy scar

When blood has lost its frenzy and its glamour.

Men in my pause shall know the cost at last

That is not to be paid in triumphs or tears,

Men will begin to judge the thing that’s past

As men will judge it in a hundred years.

Nations! whose ravenous engines must be fed

Endlessly with the father and the son,

My naked light upon your darkness, dread!—

By which ye shall behold what ye have done:

Whereon, more like a vulture than a dove,

Ye set my seal in hatred, not in love.

II.

Let no man call me good. I am not blest.

My single virtue is the end of crimes,

I only am the period of unrest,

The ceasing of the horrors of the times;

My good is but the negative of ill,

Such ill as bends the spirit with despair,

Such ill as makes the nations’ soul stand still

And freeze to stone beneath its Gorgon glare.

Be blunt, and say that peace is but a state

Wherein the active soul is free to move,

And nations only show as mean or great

According to the spirit then they prove.—

O which of ye whose battle-cry is Hate

Will first in peace dare shout the name of Love?

(1918)

Eleanor Farjeon (1881-1965)

Wilfred Owen

Futility

Move him into the sun—

Gently its touch awoke him once,

At home, whispering of fields half-sown.

Always it woke him, even in France,

Until this morning and this snow.

If anything might rouse him now

The kind old sun will know.

Think how it wakes the seeds—

Woke once the clays of a cold star.

Are limbs, so dear-achieved, are sides

Full-nerved, still warm, too hard to stir?

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

—O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earth's sleep at all?

Wilfred Owen

Anthem for Doomed Youth

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

— Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,—

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls' brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

Wilfred Owen

Disabled

He sat in a wheeled chair, waiting for dark,

And shivered in his ghastly suit of grey,

Legless, sewn short at elbow. Through the park

Voices of boys rang saddening like a hymn,

Voices of play and pleasure after day,

Till gathering sleep had mothered them from him.

About this time Town used to swing so gay

When glow-lamps budded in the light-blue trees,

And girls glanced lovelier as the air grew dim,—

In the old times, before he threw away his knees.

Now he will never feel again how slim

Girls' waists are, or how warm their subtle hands,

All of them touch him like some queer disease.

There was an artist silly for his face,

For it was younger than his youth, last year.

Now, he is old; his back will never brace;

He's lost his colour very far from here,

Poured it down shell-holes till the veins ran dry,

And half his lifetime lapsed in the hot race

And leap of purple spurted from his thigh.

One time he liked a blood-smear down his leg,

After the matches carried shoulder-high.

It was after football, when he'd drunk a peg,

He thought he'd better join. He wonders why.

Someone had said he'd look a god in kilts.

That's why; and maybe, too, to please his Meg,

Aye, that was it, to please the giddy jilts,

He asked to join. He didn't have to beg;

Smiling they wrote his lie: aged nineteen years.

Germans he scarcely thought of, all their guilt,

And Austria's, did not move him. And no fears

Of Fear came yet. He thought of jewelled hilts

For daggers in plaid socks; of smart salutes;

And care of arms; and leave; and pay arrears;

Esprit de corps; and hints for young recruits.

And soon, he was drafted out with drums and cheers.

Some cheered him home, but not as crowds cheer Goal.

Only a solemn man who brought him fruits

Thanked him; and then inquired about his soul.

Now, he will spend a few sick years in institutes,

And do what things the rules consider wise,

And take whatever pity they may dole.

Tonight he noticed how the women's eyes

Passed from him to the strong men that were whole.

How cold and late it is! Why don't they come

And put him into bed? Why don't they come?

Wilfred Owen

Smile, Smile, Smile

Head to limp head, the sunk-eyed wounded scanned

Yesterday's Mail; the casualties (typed small)

And (large) Vast Booty from our Latest Haul.

Also, they read of Cheap Homes, not yet planned;

’For’, said the paper, ‘when this war is done

The men's first instinct will be making homes.

Meanwhile their foremost need is aerodromes,

It being certain war has just begun.

Peace would do wrong to our undying dead,—

The sons we offered might regret they died

If we got nothing lasting in their stead.

We must be solidly indemnified.

Though all be worthy Victory which all bought.

We rulers sitting in this ancient spot

Would wrong our very selves if we forgot

The greatest glory will be theirs who fought,

Who kept this nation in integrity.’

Nation?—The half-limbed readers did not chafe

But smiled at one another curiously

Like secret men who know their secret safe.

(This is the thing they know and never speak,

That England one by one had fled to France

Not many elsewhere now save under France).

Pictures of these broad smiles appear each week,

And people in whose voice real feeling rings

Say: How they smile! They're happy now, poor things.

Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

Source: Poetry Foundation (US)

Links

Ivor Gurney Society, manuscripts.

Tim Kendall on Ivor Gurney.

Ivor Gurney biography and poems at the Poetry Foundation (US).

First World War Poetry digital archive.

Wilfred Owen biography and poems at the Poetry Foundation (US).

Rudyard Kipling, ‘Mary Postgate’ (1915), on Kipling Society website. This story can also be found in the story collection, A Diversity of Creatures.

Great War Fiction blog by George Simmers

Brian Clayton, English Association pamphlet on Women and the First World War (2014)

Poppies photo: Shokoofeh Poorreza, Unsplash

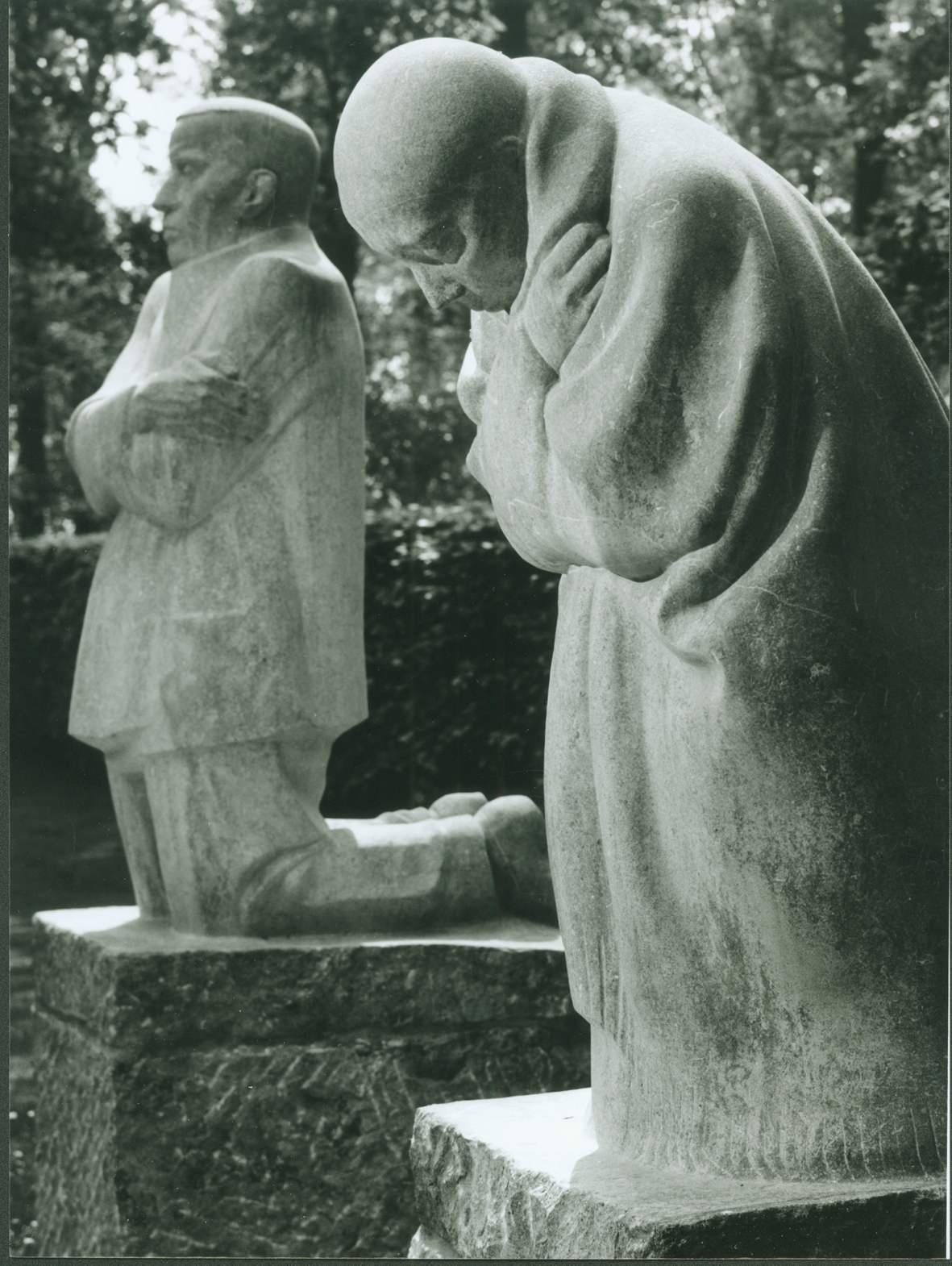

Käthe Kollwitz, Die trauendern Eltern

(The grieving parents)