Beth Daugherty on Woolf's Manuscript

Guest Blog: Beth Daugherty

Virginia Woolf summer course 2018: Woolf and Politics.

Beth gave a terrific talk on 4 July 2018 about her experiences of working on the manuscript of Virginia Woolf’s Women & Fiction (later published as A Room of One’s Own, 1929) in the Fitzwilliam Museum. She also gave some general thoughts on what scholars do when they work with manuscripts. This is an edited version of the talk.

How should one read a manuscript?

Let me count the ways . . .

Some Preliminaries

Trudi asked me to talk with you today because I spent four June days looking at the Women & Fiction manuscript in the Fitzwilliam Museum. Before I start, I want to thank the Museum for allowing me to examine the Woolf’s manuscript and Suzanne Reynolds, Nicholas Robinson, and Lucinda Green for all their help.

I am working on Woolf’s essays, and although I have looked at many of her essay manuscripts in the past – reading notes, drafts, typescripts – I’ve never had the opportunity to look at this extended essay draft until this summer. In this talk I want to explore the following questions and to think about what scholars do in archives:

1) Why do scholars work with manuscripts and typescripts?

2) What do scholars look for when they work with manuscripts?

3) What did I see in this manuscript, Women & Fiction?

Why work with manuscripts and typescripts?

Why?

– There’s simply nothing else like it.

– There is a desire to know, get closer to writer, even if only in imagination, add to knowledge about a writer.

– To see the ‘how’ and perhaps the ‘why’ behind the ‘what’ – what was the process like?

– To learn more about the writing process in general; it’s encouraging to see Woolf working through ideas on paper, jettisoning passages, moving things around, trying out things, etc. (I am not like Lamb – seeing her at work does not lessen her in my eyes at all; quite the opposite).

– To become a detective searching for clues.

– To fill out context about people who lived and worked in the past, not just Woolf, but those around her: book manuscripts, correspondence, unpublished drafts, juvenilia, diaries, memoirs, etc. bring them back to life.

– Sometimes for a practical reason: to complete a sentence, finish an endnote.

– Sometimes for a thrilling reason: you’ve discovered a manuscript (as S. P. Rosenbaum did) or a typescript or a bit of information that no one else seems to know about; or you see something in a manuscript that others haven’t.

– They’re there, it’s fun – and fascinating.

What do scholars ‘do’ when they work with manuscripts?

– What do we actually do? We look at everything! (every scrap of paper, front and back); sit with materials, get used to handwriting, peer, try to read, read; do fine, get stopped by a word you can’t read, use magnifying glass, trace letters in air or on paper; take notes on laptop; stay awake (ha!); later, think about what you saw, what it meant.

– Pay attention to revisions, to stops and starts, to repetition, to cuts, to differences between draft and final published version, to first appearances (Mary Arden becomes Judith Shakespeare).

– Collect information, support, supplementary tidbits for an article or book of your own.

– Transcribe: write/type out what you see, add revisions, prepare a transcription to refer to as you do your own work at home or prepare a transcription for publication as S. P. Rosenbaum did.

– Check other transcriptions, see for yourself, which was what I was doing here: checking S. P. (Pat) Rosenbaum’s transcription, absorbing his work, seeing I could trust it (only a few differing readings and a few gaps I could fill, but a remarkably clean, accurate transcription); also observing Woolf’s work, wondering if any connections to my project; can I use what I saw? not sure yet . . .

– Make editorial decisions for an edition: different versions (British and American first editions of Woolf texts differ!), different revisions, what should the text for a new edition be? and why? scholar has to decide and justify decision, because it affects what readers read and how they interpret.

– Look for? sometimes you have no idea: you don’t know until you look.

– Sometimes looking for something in particular – who is Miss Clay? – sometimes looking for something in general – what was Virginia Stephen’s teaching schedule like at Morley College? –sometimes don’t know what you’re looking for, like with this manuscript.

What did I see in this manuscript, Women & Fiction?

Woolf writes:

‘This led me to remember what I could of Lycidas and to amuse myself with guessing which word it could have been that Milton had altered, and why. [. . . ] [or, in the case of Thackeray’s Esmond, seeing whether] the eighteenth-century style was natural to Thackeray [or] seeing whether the alterations were for the benefit of the style or of the sense.’ (A Room of One's Own, 6-7)

Some background: Leonard Woolf was asked by the Director of the Fitzwilliam for something of Virginia Woolf’s. As Pat Rosenbaum says, he ‘responded appropriately and with great generosity, giving back to Cambridge . . . the manuscript that had its beginning there’ (xiii), and Leonard clearly identified the manuscript as the first draft of Virginia’s A Room of One’s Own. It then lay ‘virtually unread’ for nearly 50 years. Pat’s report that he was told ‘It is mentioned in our annual report for 1942’ and his comment, ‘and so it is’ (x) is cryptic, conveying both bewilderment and a reluctance or inability to say any more. The defensive comment made by someone at the Fitzwilliam does not seem like much of a defence. After all, not many scholars read archival annual reports. But the manuscript arrived in war time, staff would have been short, overworked, and working on other priorities, and I suspect the letter got separated from the manuscript. Whatever the reasons – they seem shrouded in mystery – the neglect ironically confirms a great deal of the content and meaning of Woolf’s book.

Pat was also well aware of the irony of being a male professor editing the manuscripts, but asked for help from several feminist Woolf scholars. Michèle Barrett criticizes him for the 2-year embargo on the text between discovery and publication of his transcription (‘A Note on the Texts,’ AROO & 3G, lvii), but I can’t say that I blame him. He would have had to get permission from the Bells, find funding for the time needed to do the work, have a publisher lined up, all before he could start, and what if he got scooped in the meantime?

After transcribing the manuscript, reading the typescript, and comparing them to the published text, Pat says Woolf makes her ‘criticism of the patriarchy’s sexual standards stronger’ in her final version than in her draft: ‘Indeed there is little in the manuscripts to suggest that Woolf is softening or censoring her text to make it more acceptable to male readers, as is sometimes claimed about her revisions’ (xl). So, for example, there is a lot more about chastity and the patriarchy’s use of it as a weapon against women in the published version than in the draft.

Pat’s work reveals the incredible speed at which Woolf wrote this book: there are some introductory pages, but then chapter 2 is dated 6 March 1929; the last page of the Conclusion is dated 2 April 1929! She started making it up in her head as she lay in bed recovering from illness, then drafted in ‘one of my excited outbursts of composition’ (Diary 3, 218-19). Beginning to revise, she wrote in her diary, ‘I used to make it up at such a rate that when I got pen & paper I was like a water bottle turned upside down. The writing was as quick as my hand could write; too quick, for I am now toiling to revise; but this way gives one freedom & lets one leap from back to back of one’s thoughts’ (Diary 3, 221-22). One reason for this speed, Woolf commented, was that ‘the thinking had been done & the writing stiffly & unsatisfactorily 4 times before’ (Diary 3 218-19; 221-22). She signed her contract with Harcourt Brace on 30 June, began The Waves two days later (!), corrected the proofs in July and August, and saw the book published in October 1929.

We now know of at least 6 stages: her lectures at Girton and Newnham; ‘Women & Fiction’ essay (published in the US Forum); Women & Fiction draft (the Fitzwilliam and Monks House Papers manuscripts transcribed by S. P. Rosenbaum); A Room of One’s Own typescript (Monks House Papers, Sussex; parts transcribed in Rosenbaum appendix); A Room of One’s Own proof copy (Berg Collection, NYC; transcribed by Isaac Gewirtz in Woolf Studies Annual, vol. 17 [2011]); A Room of One’s Own text, published by Hogarth Press & Harcourt Brace, October 1929.

So what did I see? Sometimes I saw Woolf in the midst of the creative process – in the margin on page 90 of Rosenbaum’s transcription, she jots down ‘incandescent’ to describe Shakespeare’s mind. Sometimes I saw her become aware of a rhetorical strategy – on page 157 of the transcription, she catches herself starting to use “but” again; on page 90 of the published Penguin edition, she scolds herself for saying it too often and then consciously uses it to pin herself down. The value of using ‘but’ to create a complex argument may also have led Woolf to change ‘The words hang like a collar round my neck’ (transcription 3) to her book’s now famous opener, ‘But, you may say, . . .’ (3), to move from an emphasis on the writer’s task to the reader’s question, to begin her book’s last sentence with ‘but’ as well (103). Sometimes I watched Woolf’s imagination take off – Judith Shakespeare’s story is one such place. Sometimes I wondered about a revision. On page 91 of the transcription, Woolf writes that Shakespeare ‘did, as far as human being ever did, get his work out of him unhurt’. In her published work, she says ‘If ever a human being got his work expressed completely, it was Shakespeare. If ever a mind was incandescent, unimpeded . . .’ (52). Lost in that revision (to me, anyway) is the loveliness of a line, a recognition of the pain connected to creativity, and a meaningful ambiguity – get the work out unhurt? get work out without hurting the self? both? Perhaps in this instance, Woolf was trying to consume an obstacle, be incandescent herself.

*

Trudi Tate writes:

We looked at several examples from the manuscript, comparing it with Rosenbaum's transcription, and with the published version of the book. We are really grateful to Beth for giving us such close insights into her scholarly work. Thanks also to Claire Nicholson for an excellent introduction to the manuscript, and to the Fitzwilliam Museum for hosting us. We will visit again on our Woolf course in 2019.

Further information about the manuscript is on the Fitzwilliam Museum website.

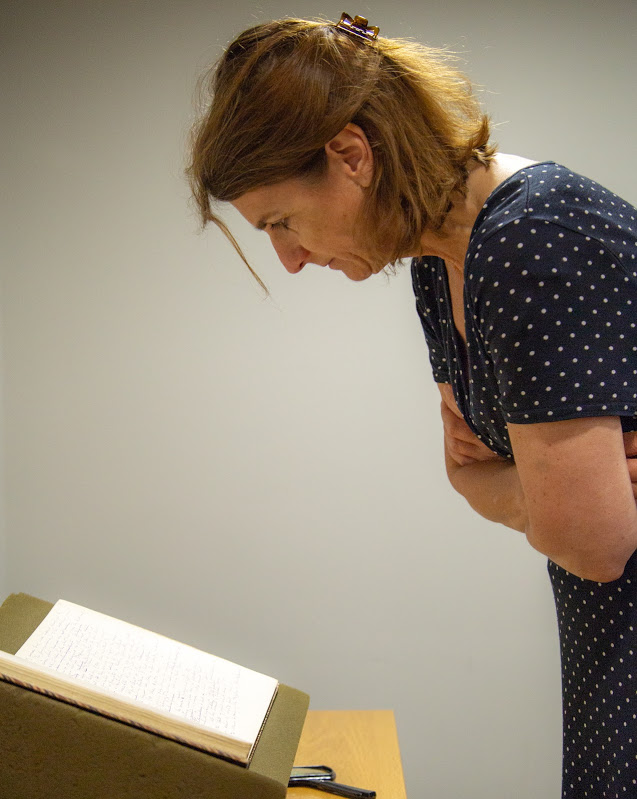

Gallery: images from our visit to the Fitzwilliam Museum to see Woolf's manuscript of A Room of One's Own, with talks by Beth Daugherty and Claire Nicholson. Thanks to Jeremy Peters @JezPete for the photographs.